=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless ===

# Documentation

Welcome to the documentation.

## Subpages

- **{{< key product_name >}} Serverless**

- **Tutorials**

- **Integrations**

- **Reference**

- **Community**

- **Architecture**

- **Platform deployment**

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide ===

# {{< key product_name >}} Serverless

{{< key product_name >}} empowers AI development teams to rapidly ship high-quality code to production by offering optimized performance, unparalleled resource efficiency, and a delightful workflow authoring experience. With {{< key product_name >}} your team can:

* Run complex AI workloads with performance, scale, and efficiency.

* Achieve millisecond-level execution times with reusable containers.

* Scale out to multiple regions, clusters, and clouds as needed for resource availability, scale, or compliance.

> [!NOTE]

> {{< key product_name >}} is built on top of the leading open-source workflow orchestrator, [Flyte](/docs/v1/flyte/).

>

> {{< key product_name >}} Serverless provides **all the features of Flyte, plus much more**

> all in a turn-key, fully-managed, cloud environment.

> There is zero infrastructure to deal with, and you pay only for the resources you use.

> Your data and workflow code is stored safely and securely in the Union.ai cloud infrastructure.

>

> You can switch to another product version with the selector above.

### 💡 **Introduction**

{{< key product_name >}} builds on the leading open-source workflow orchestrator, Flyte, to provide a powerful, scalable, and flexible platform for AI applications.

### 🔢 **Getting started**

Build your first {{< key product_name >}} workflow, exploring the major features of the platform along the way.

### 🔗 **Core concepts**

Understand the core concepts of the {{< key product_name >}} platform.

### 🔗 **Development cycle**

Explore the {{< key product_name >}} development cycle from experimentation to production.

### 🔗 **Data input/output**

Manage the input and output of data in your {{< key product_name >}} workflow.

### 🔗 **Programming**

Learn about {{< key product_name >}}-specific programming constructs.

## Subpages

- **Introduction**

- **Getting started**

- **Core concepts**

- **Development cycle**

- **Data input/output**

- **Administration**

- **Programming**

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/introduction ===

# Introduction

{{< key product_name >}} unifies your AI development on a single end-to-end platform, bringing together data, models and compute with workflows of execution on a single pane of glass.

{{< key product_name >}} builds on [Flyte](https://flyte.org), the open-source standard for orchestrating AI workflows.

It offers all the features of Flyte while adding more capability to scale, control costs and serve models.

There are three deployment options for {{< key product_name >}}: **Serverless**, **BYOC** (Bring Your Own Cloud), and **Self-managed**.

## Flyte

Flyte provides the building blocks need for an end-to-end AI platform:

* Reusable, immutable tasks and workflows

* Declarative task-level resource provisioning

* GitOps-style versioning and branching

* Strongly-typed interfaces between tasks enabling more reliable code

* Caching, intra-task checkpointing, and spot instance provisioning

* Task parallelism with *map tasks*

* Dynamic workflows created at runtime for process flexibility

Flyte is open source and free to use.

You can switch to the Flyte docs [here](/docs/v1/flyte/).

You can try out Flyte's technology:

* In the cloud with [{{< key product_name >}} Serverless](https://signup.union.ai).

* On your machine with a **Development cycle > Running in a local cluster**.

For production use, you have to **Platform deployment**.

## {{< key product_name >}} Serverless

[{{< key product_name >}} Serverless](/docs/v1/serverless/) is a turn-key solution that provides a fully managed cloud environment for running your workflows.

There is zero infrastructure to manage, and you pay only for the resources you use.

Your data and workflow code is stored safely and securely in {{< key product_name >}}'s cloud infrastructure.

{{< key product_name >}} Serverless provides:

* **All the features of Flyte**

* Granular, task-level resource monitoring

* Fine-grained role-based access control (RBAC)

* Faster performance:

* Launch plan caching: Cache launch plans, 10-100x speed-up

* Optimized Propeller: more than 10 core optimizations

* Faster cache: Revamped caching subsystem for 10x faster performance

* Accelerated datasets: Retrieve repeated datasets and models more quickly

* Faster launch plan resolution

* Reusable containers (do not pay the pod spin-up penalty)

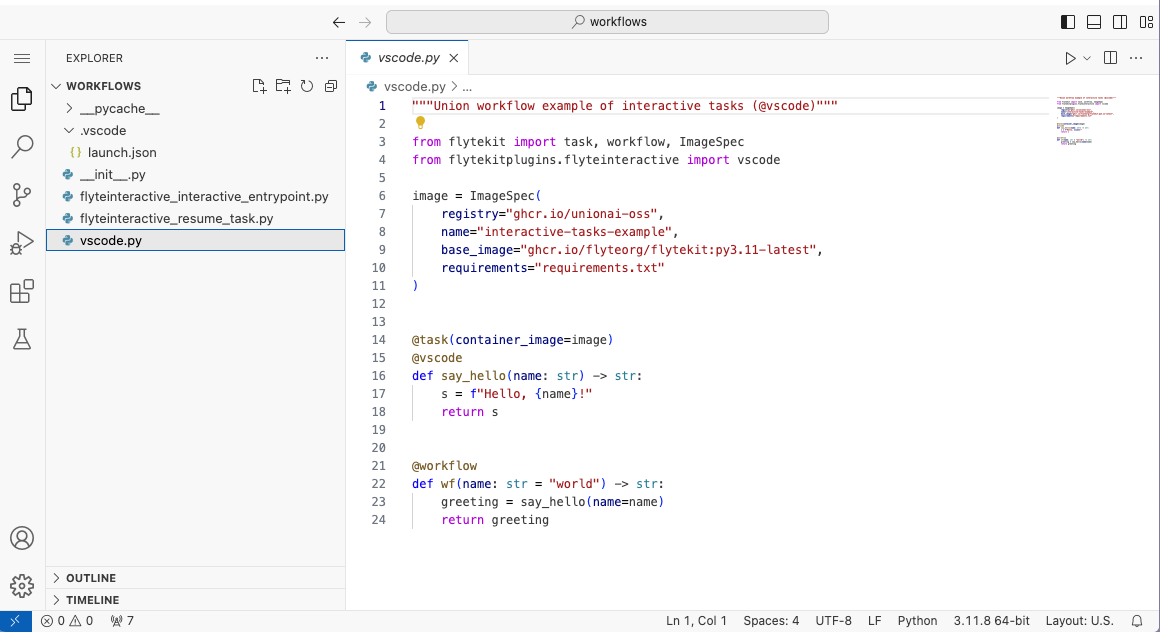

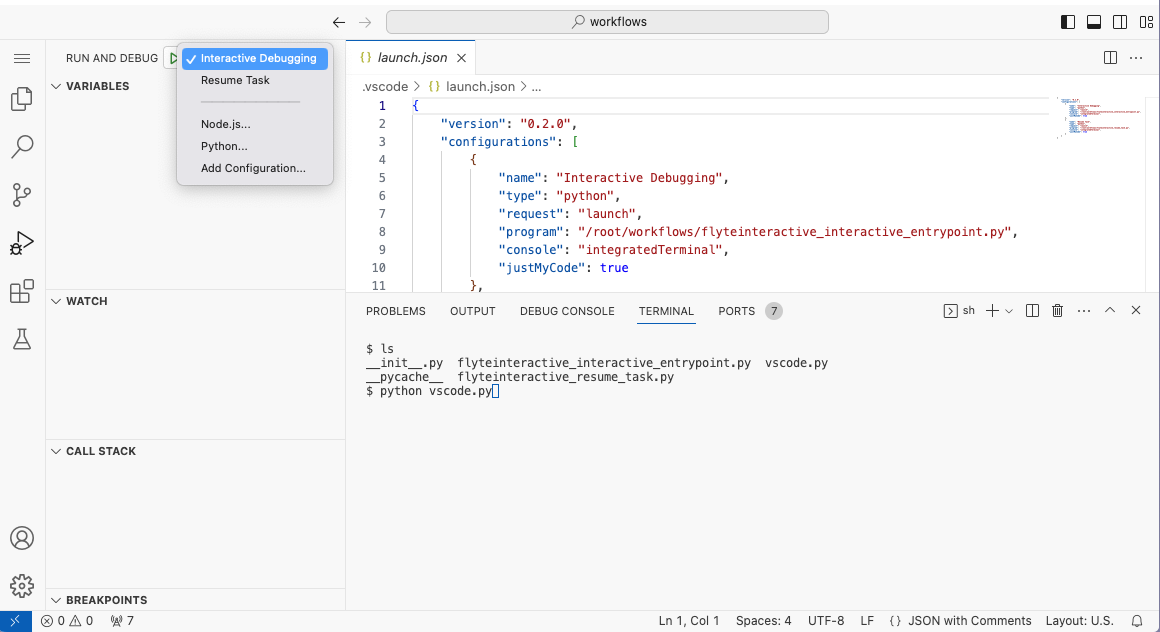

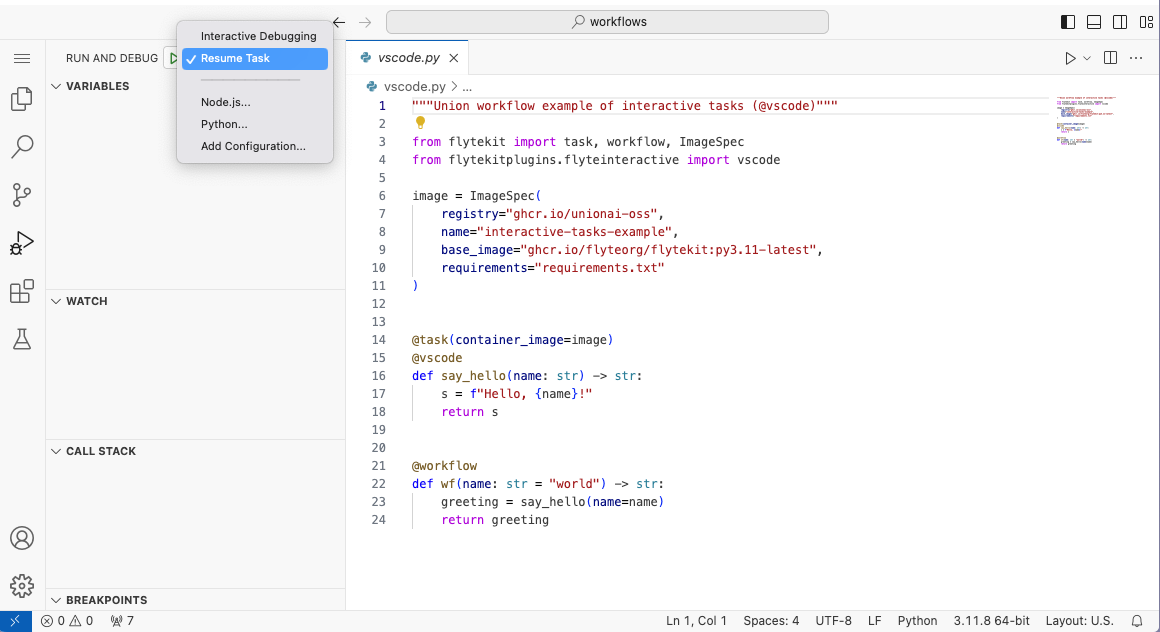

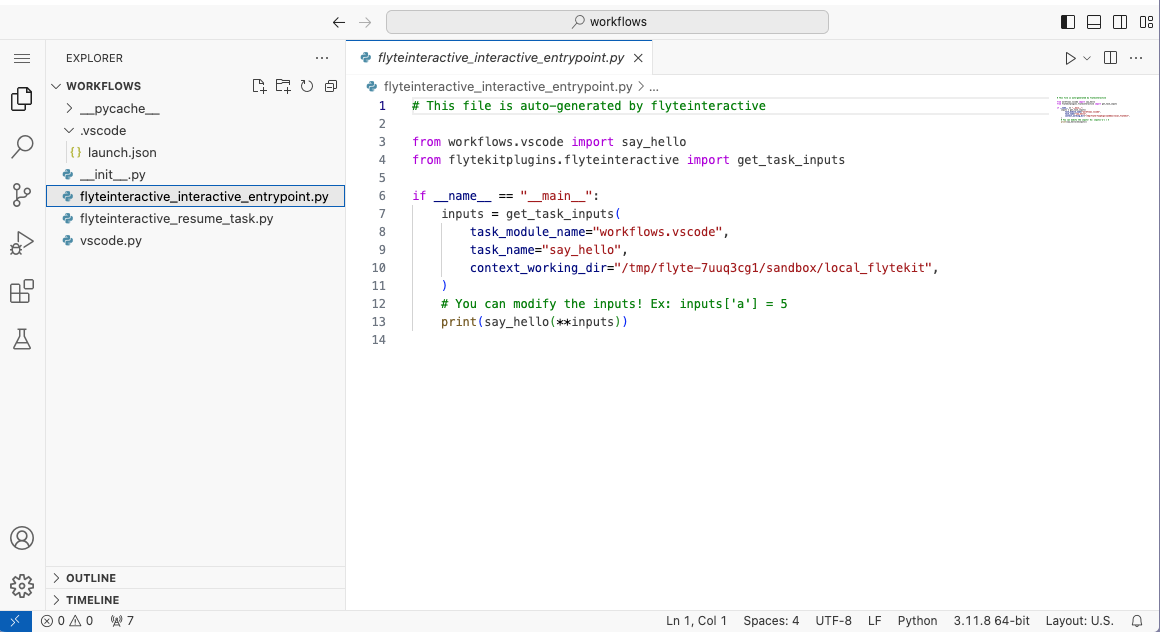

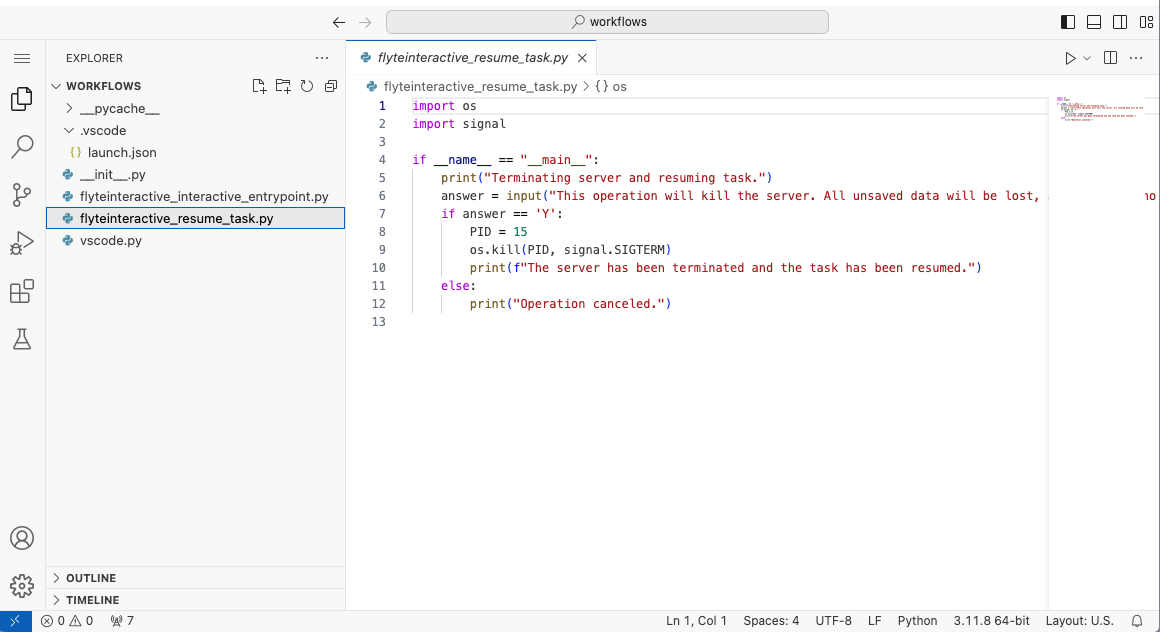

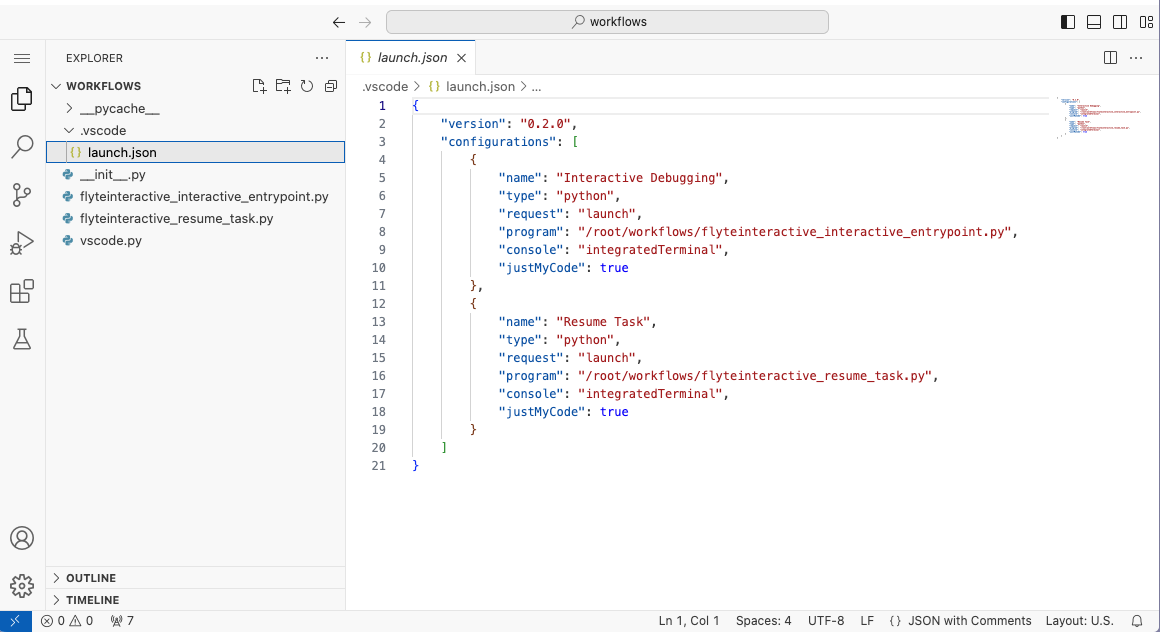

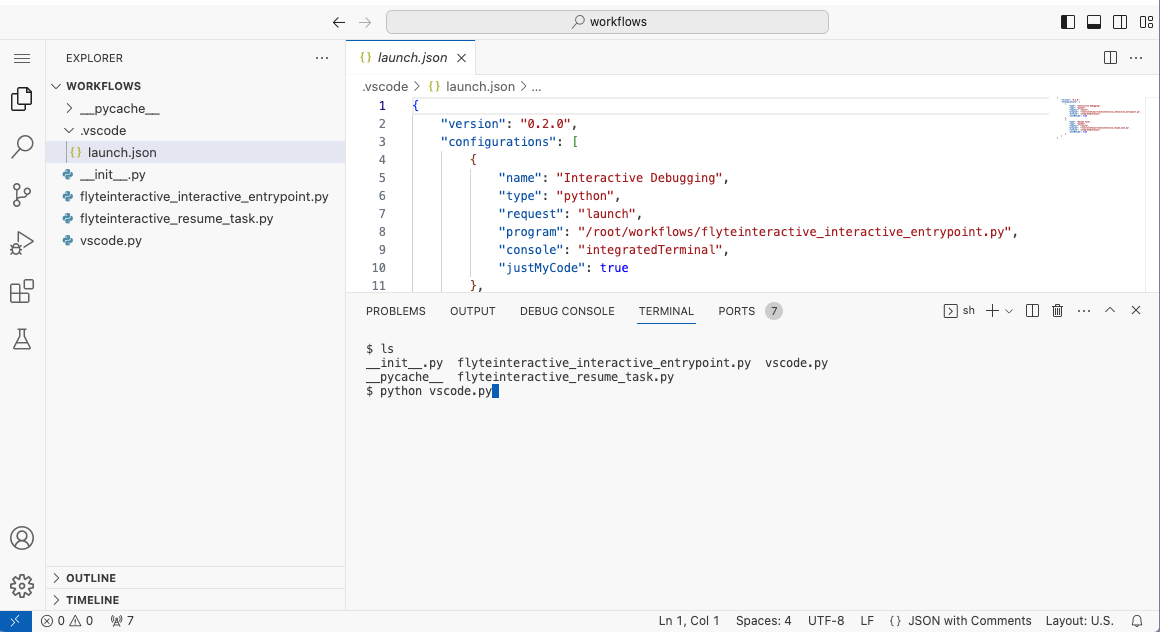

* Interactive tasks:

* Edit, debug and run tasks right in the pod through VS Code in the browser

* Artifacts discovery and lineage

* Reactive workflows:

* Launch plans trigger (and kick off workflows) on artifact creation

* Smart defaults and automatic linking

* UI based workflow builder

## {{< key product_name >}} BYOC

[{{< key product_name >}} BYOC](/docs/v1/byoc/) (Bring Your Own Cloud) lets you keep your data and workflow code on your infrastructure, while {{< key product_name >}} takes care of the management.

{{< key product_name >}} BYOC provides:

* **All the features of Flyte**

* **All the features of {{< key product_name >}} Serverless**

* Accelerators and GPUs (including fractional GPUs)

* Managed Ray and Spark

* Multi-cluster and multi-cloud

* Single sign-on (SSO)

* SOC-2 Type 2 compliance

## {{< key product_name >}} Self-managed

[{{< key product_name >}} Self-managed](/docs/v1/selfmanaged/) lets you keep full control of your data, code, and infrastructure.

{{< key product_name >}} Self-managed provides:

* **All the features of Flyte**

* **All the features of {{< key product_name >}} Serverless**

* **All the features of {{< key product_name >}} BYOC**

The only difference between {{< key product_name >}} BYOC and {{< key product_name >}} Self-managed is that

with Self-managed you are responsible for the system infrastructure, either partially or fully, according to which option you choose:

* Deploy and manage your data plane yourself on your infrastructure while Union.ai manages the control plane on our infrastructure.

* Deploy and manage both your data plane and control plane on your infrastructure with support and guidance from Union.ai.

This option is suitable for air-gapped deployments.

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/getting-started ===

# Getting started

This section gives you a quick introduction to writing and running {{< key product_name >}} workflows.

## Sign up for {{< key product_name >}} Serverless

First, sign up for {{< key product_name >}} Serverless:

{{< button-link text="Create an account" target="https://signup.union.ai/" variant="warning" >}}

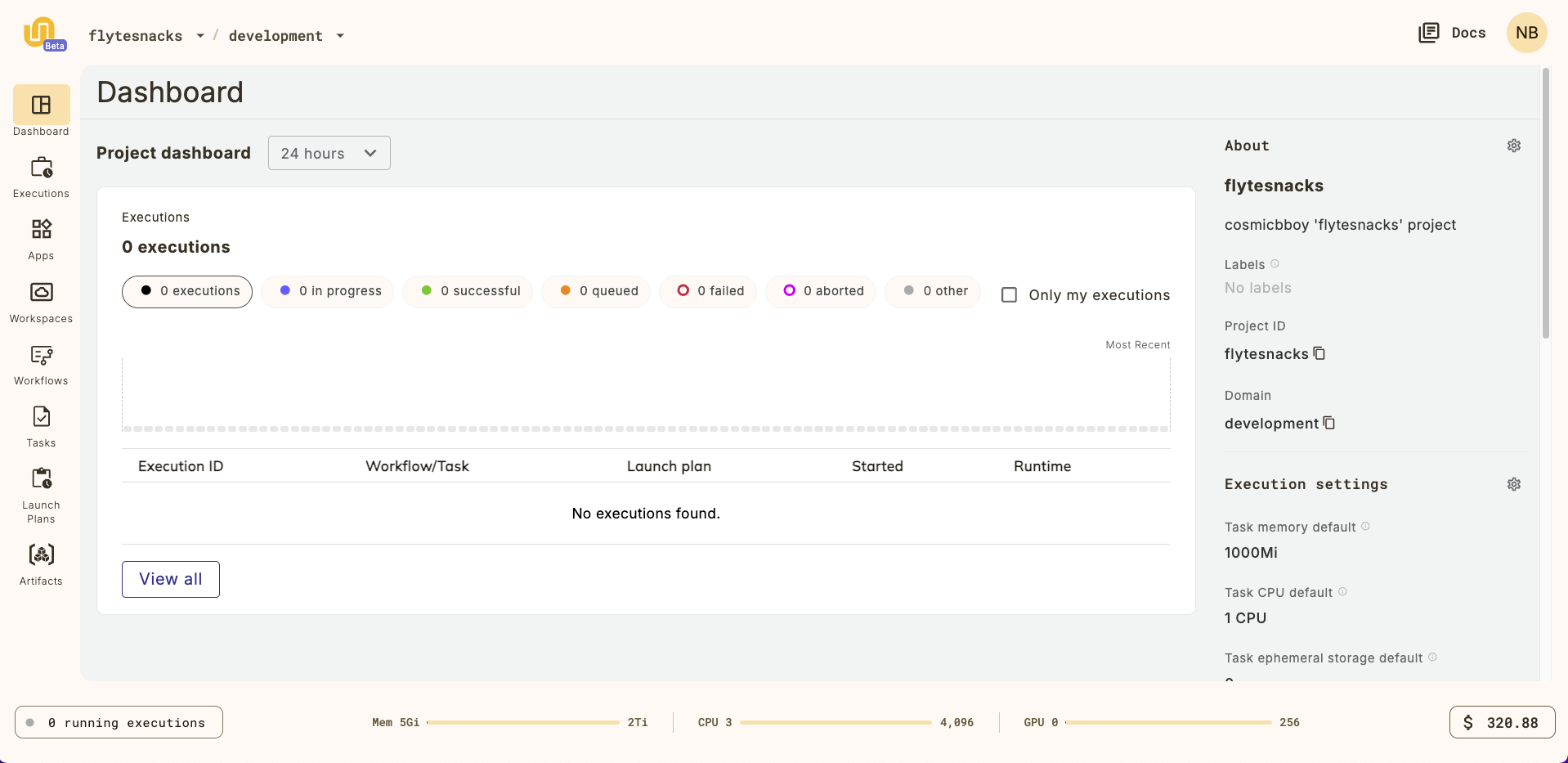

Once you've received confirmation that your sign-up succeeded, navigate to

the UI at [serverless.union.ai](https://serverless.union.ai).

To get started, try selecting the default project, called `{{< key default_project >}}`, from the list of projects.

This will take you to `{{< key default_project >}}` project dashboard:

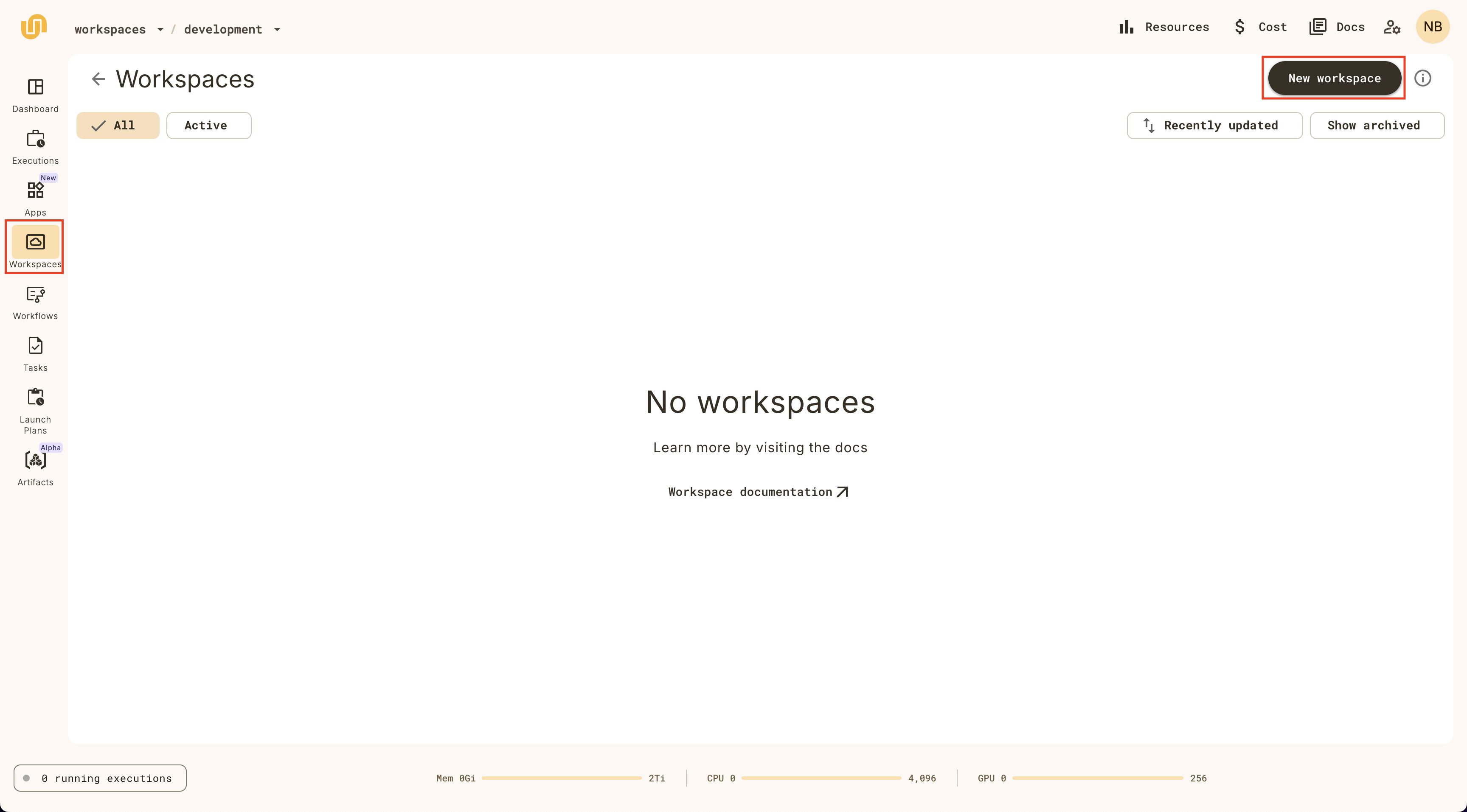

## Run your first workflow

Run your first workflow on a {{< key product_name >}} Workspace.

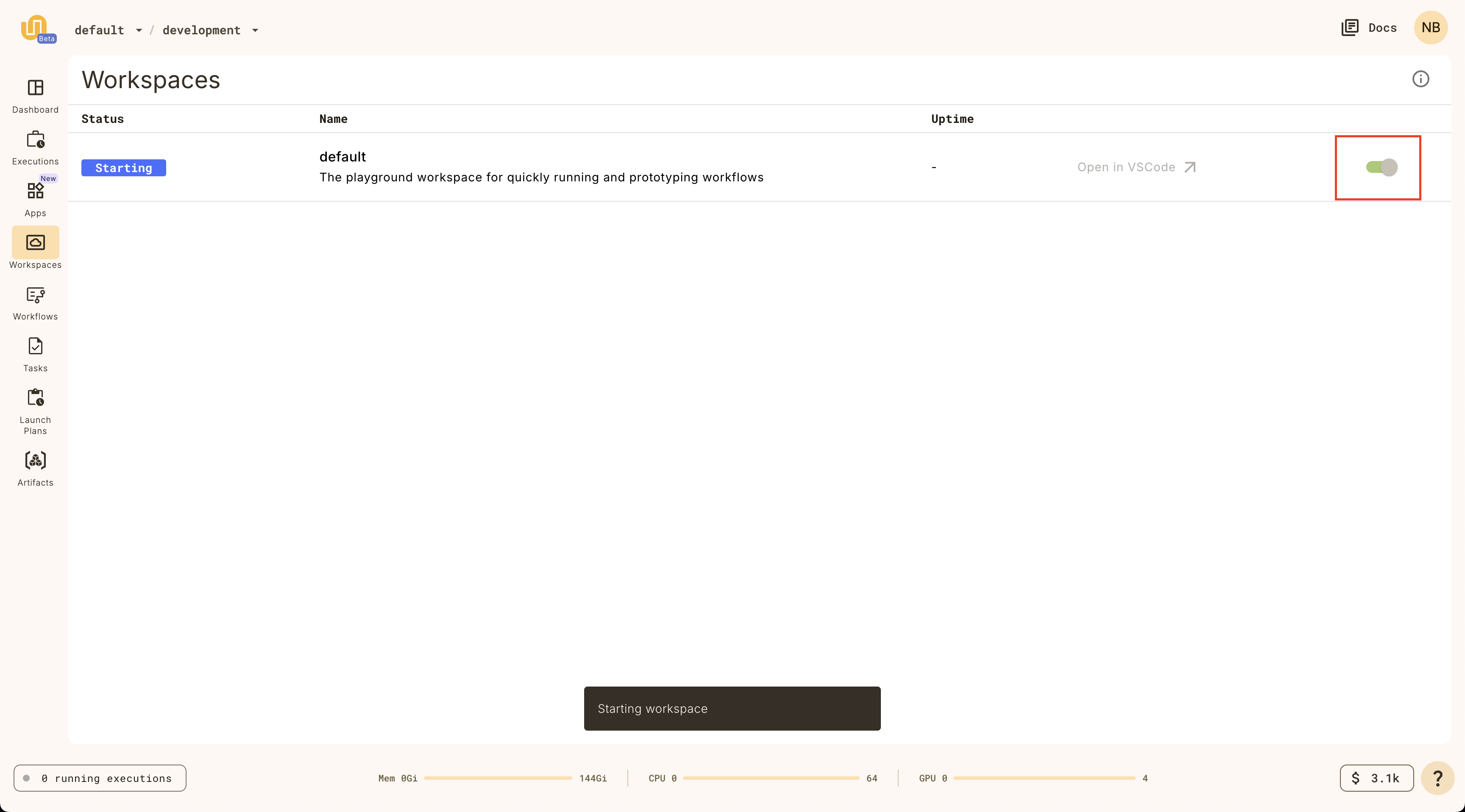

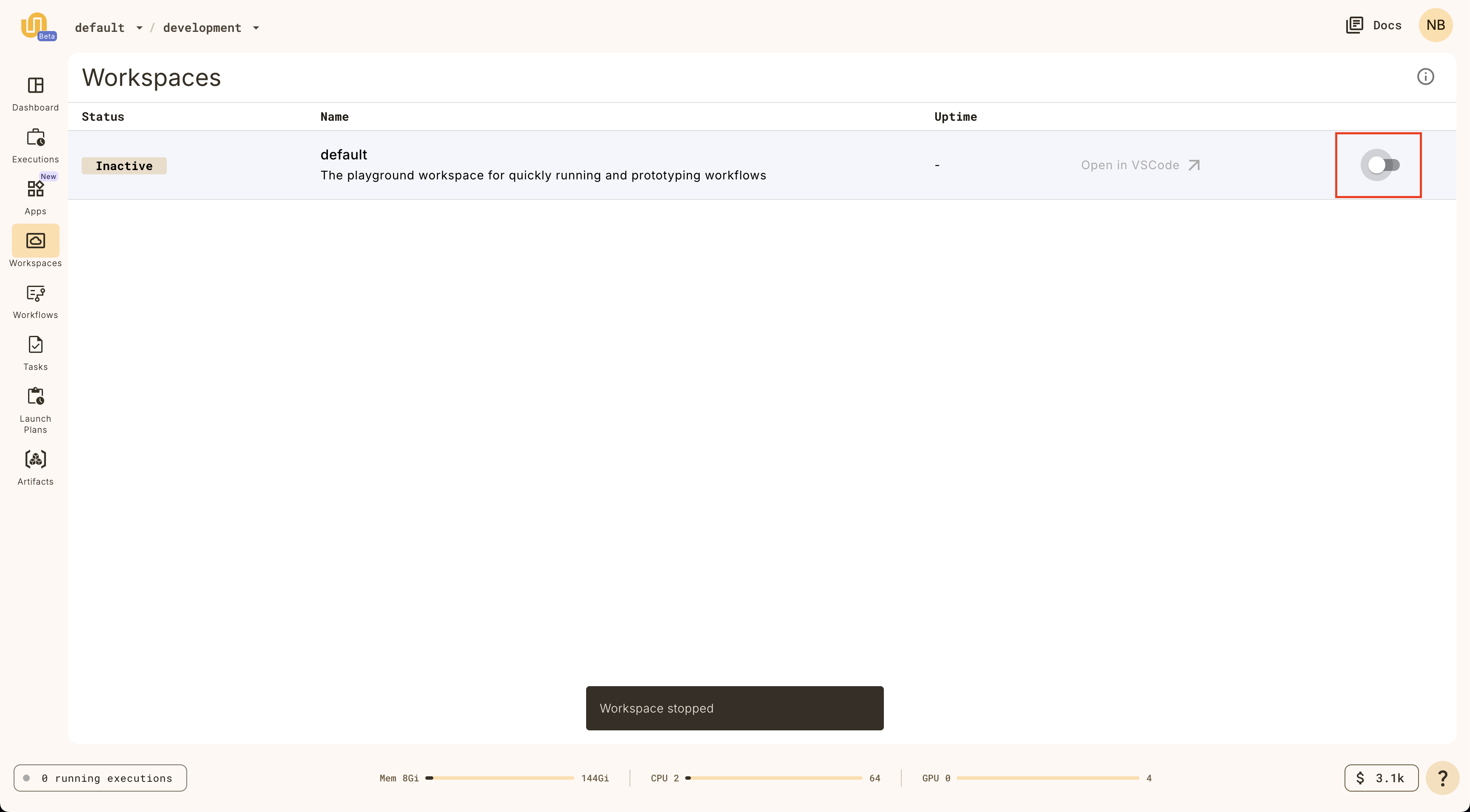

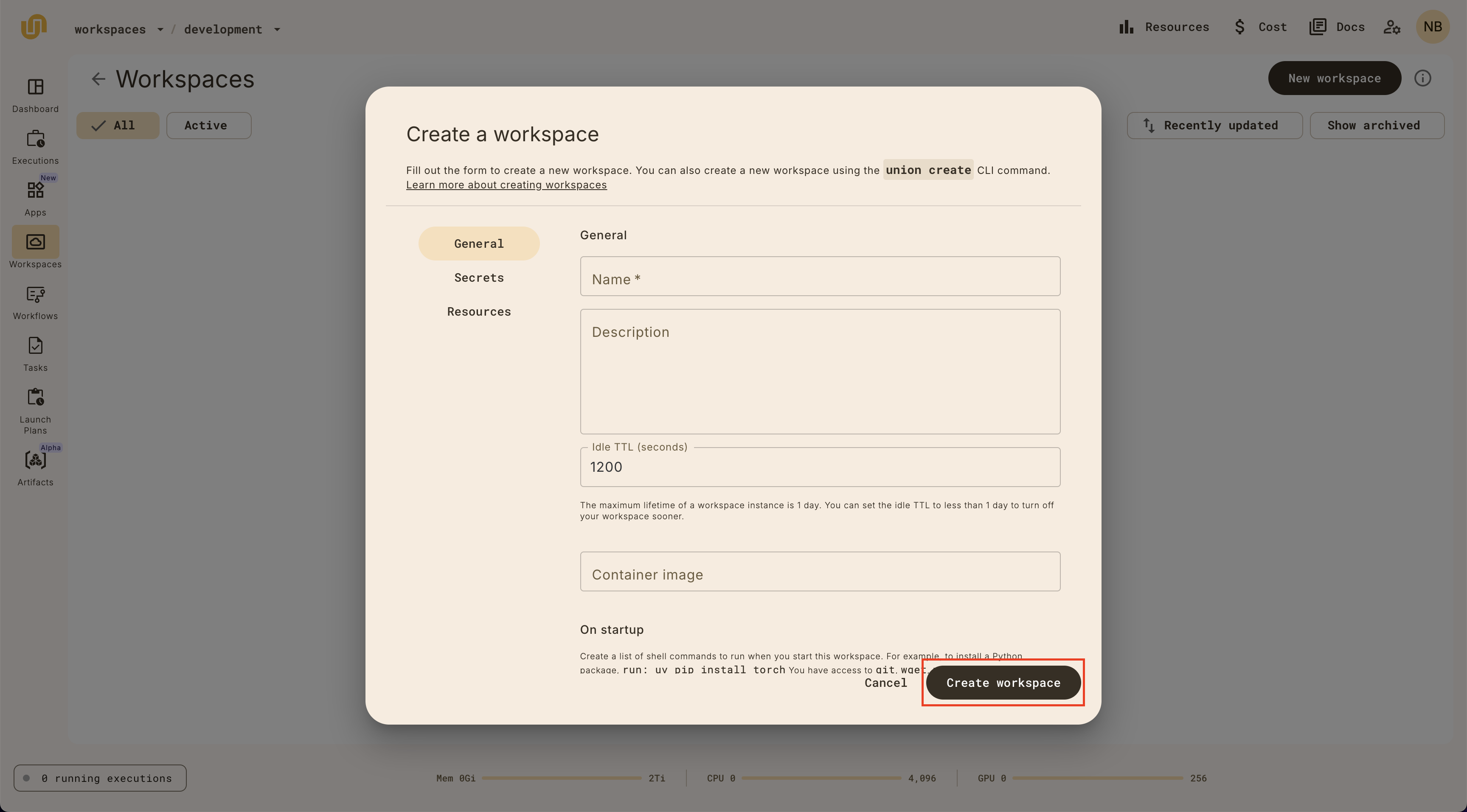

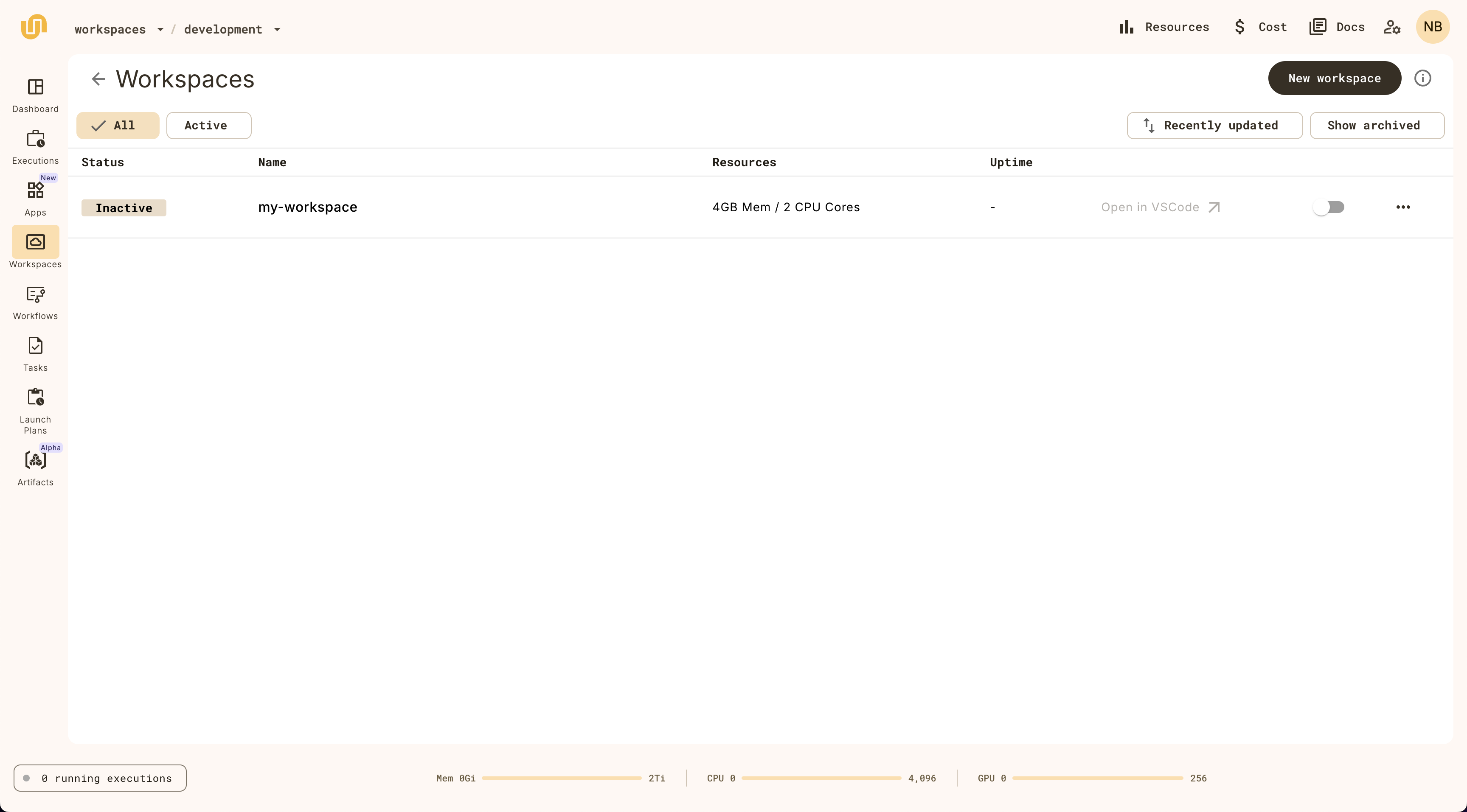

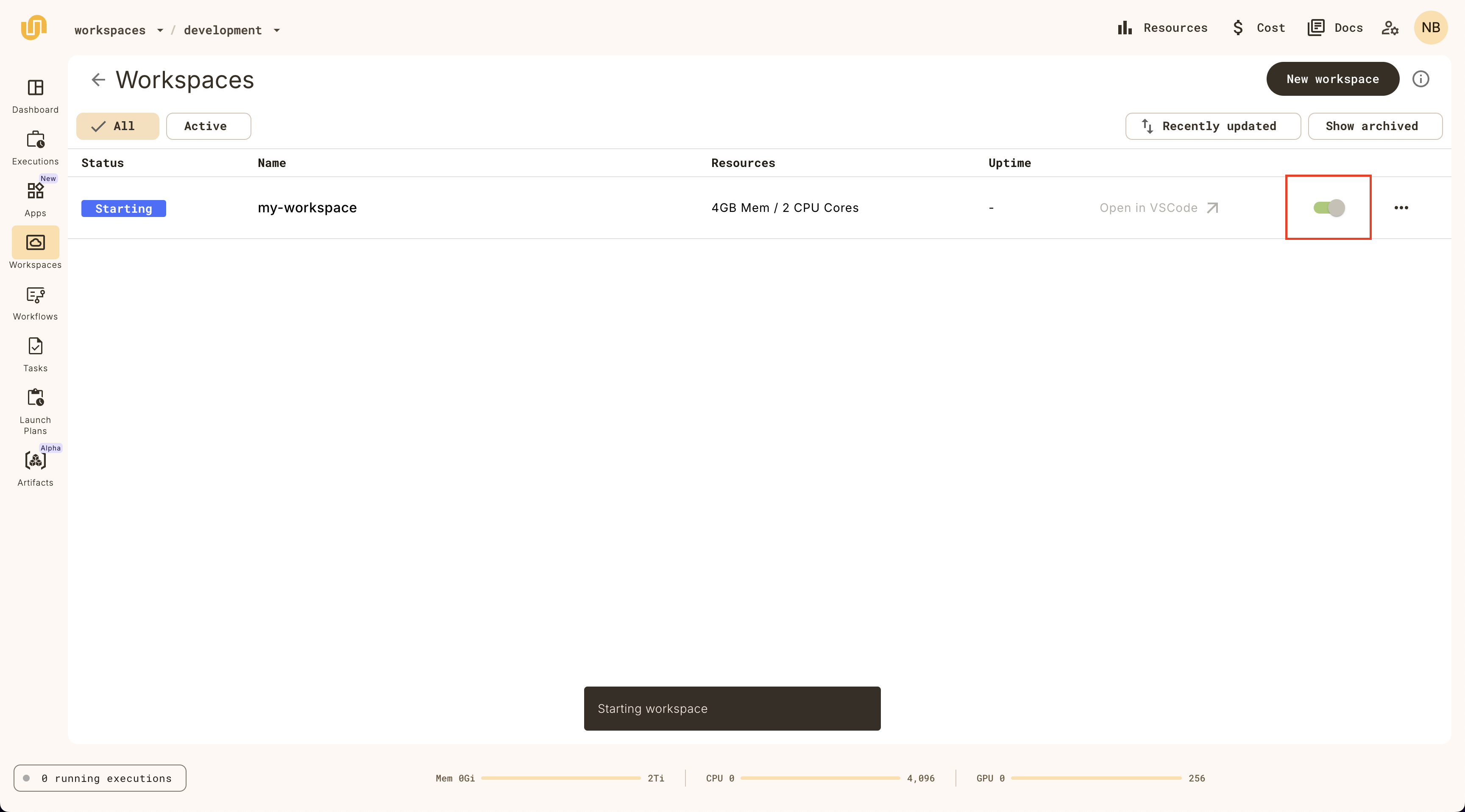

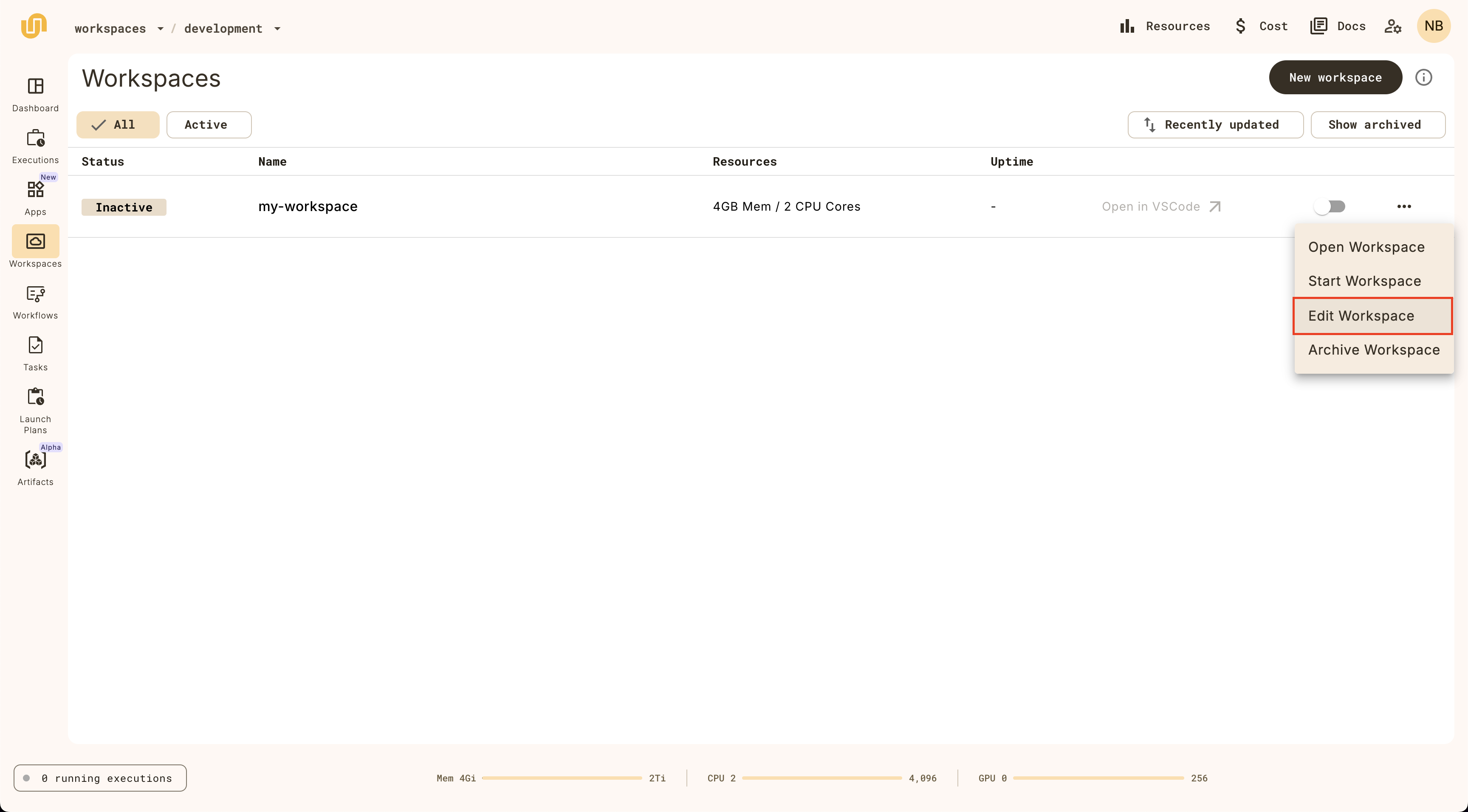

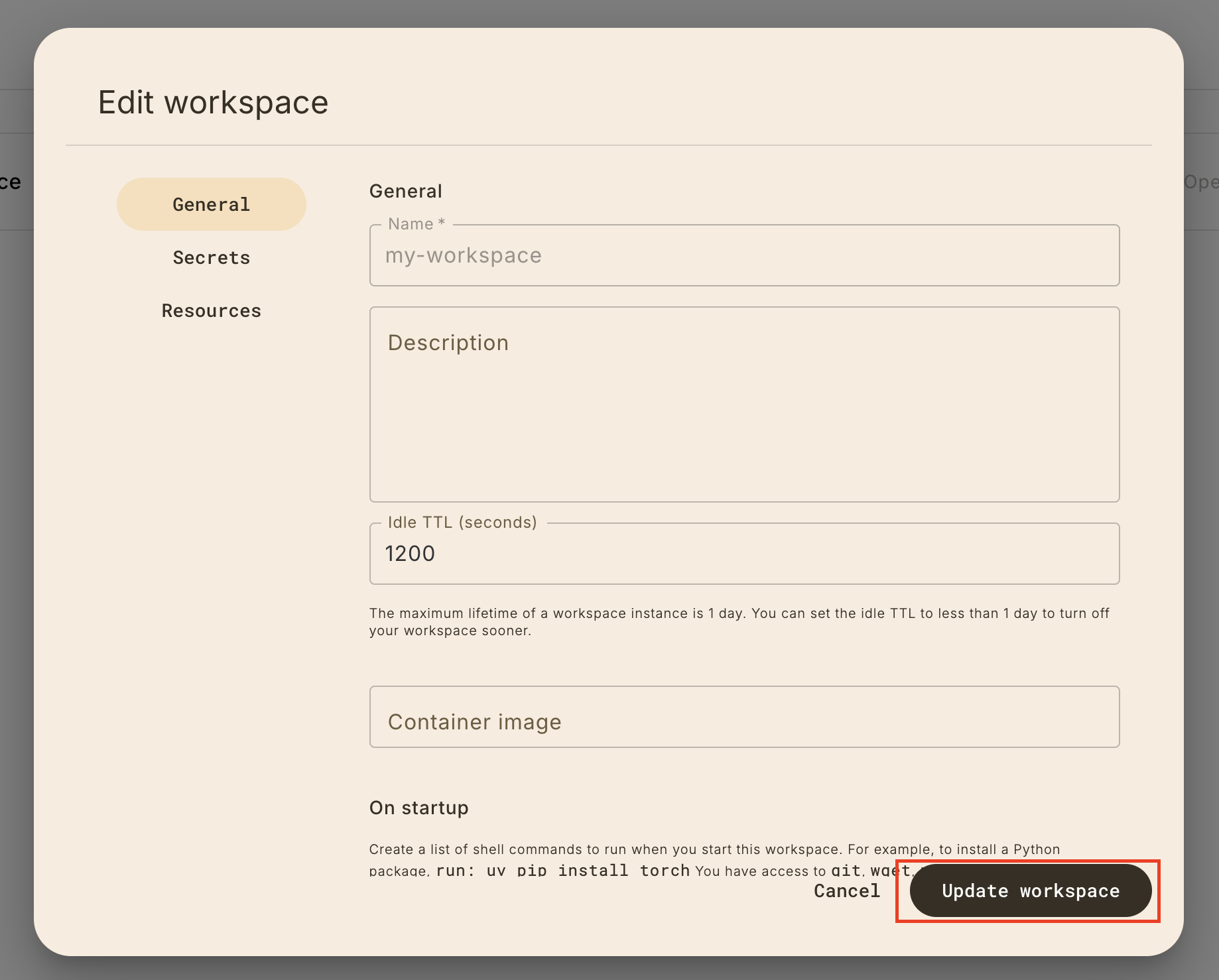

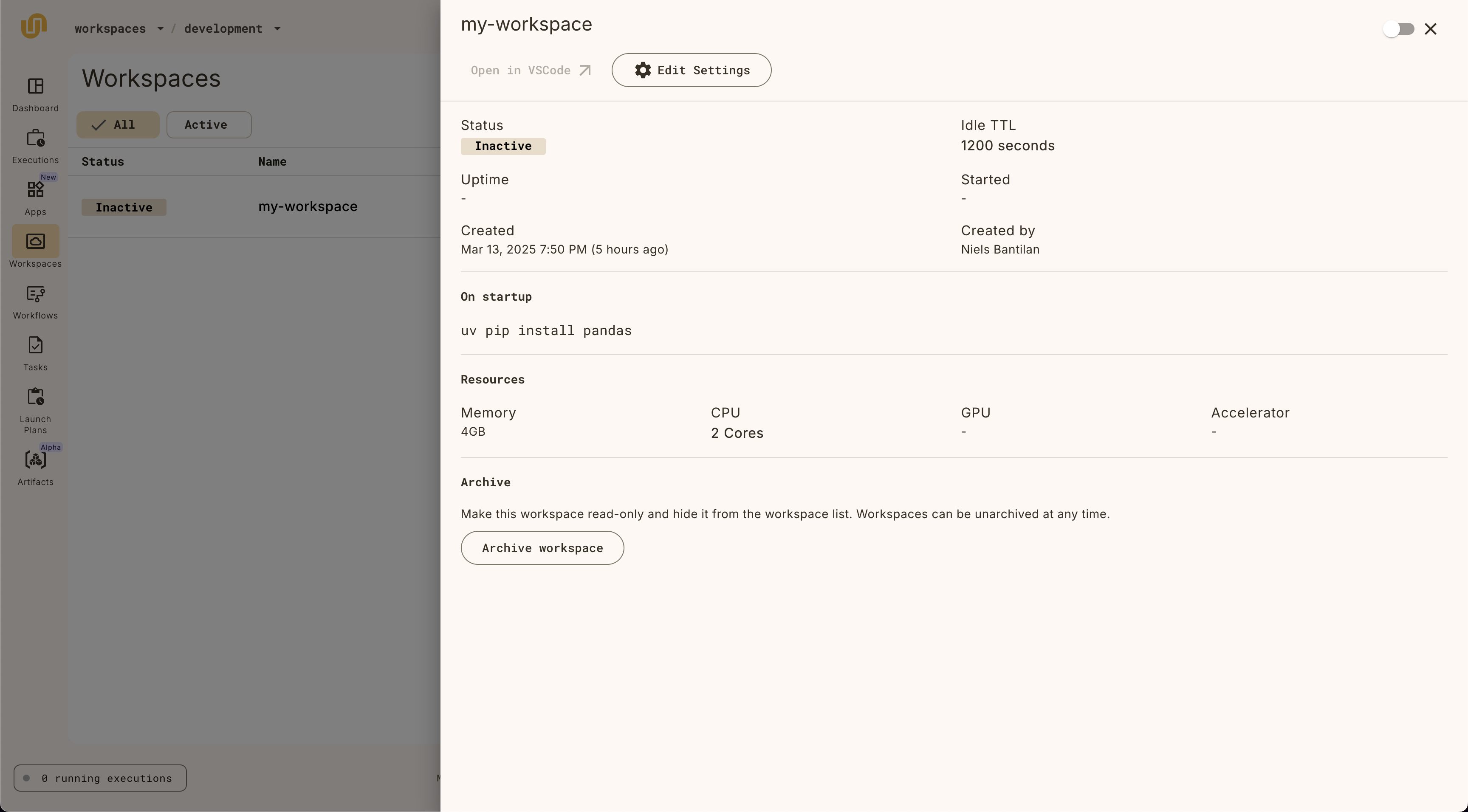

Start workspace

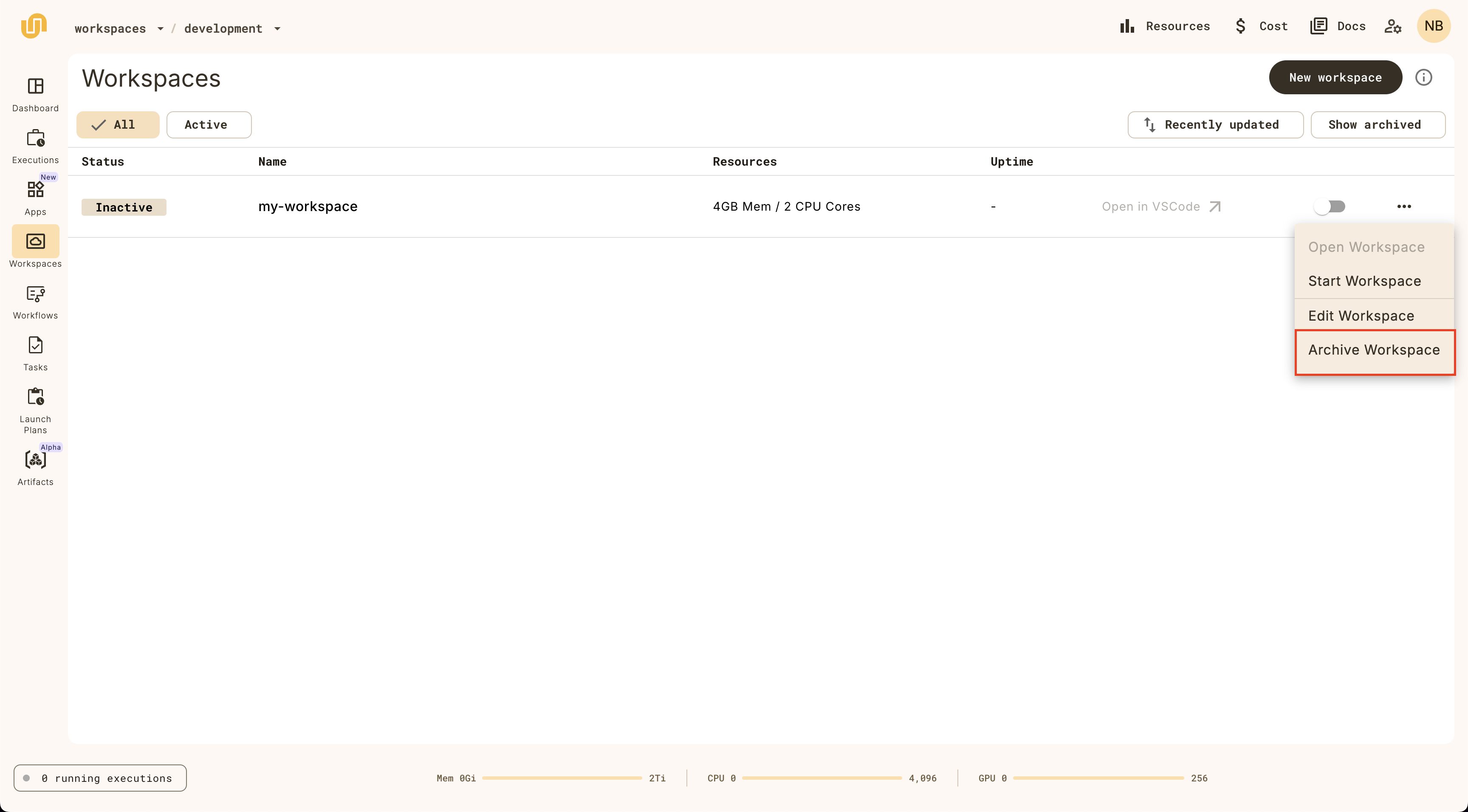

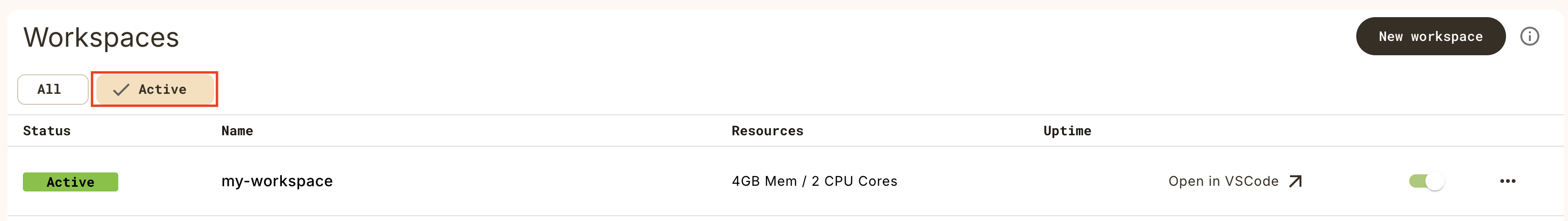

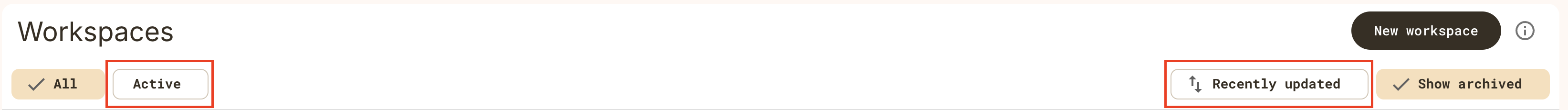

Select **Workspaces** in the left navigation bar.

Start the default workspace by clicking on the `default` workspace item.

)

Open workspace

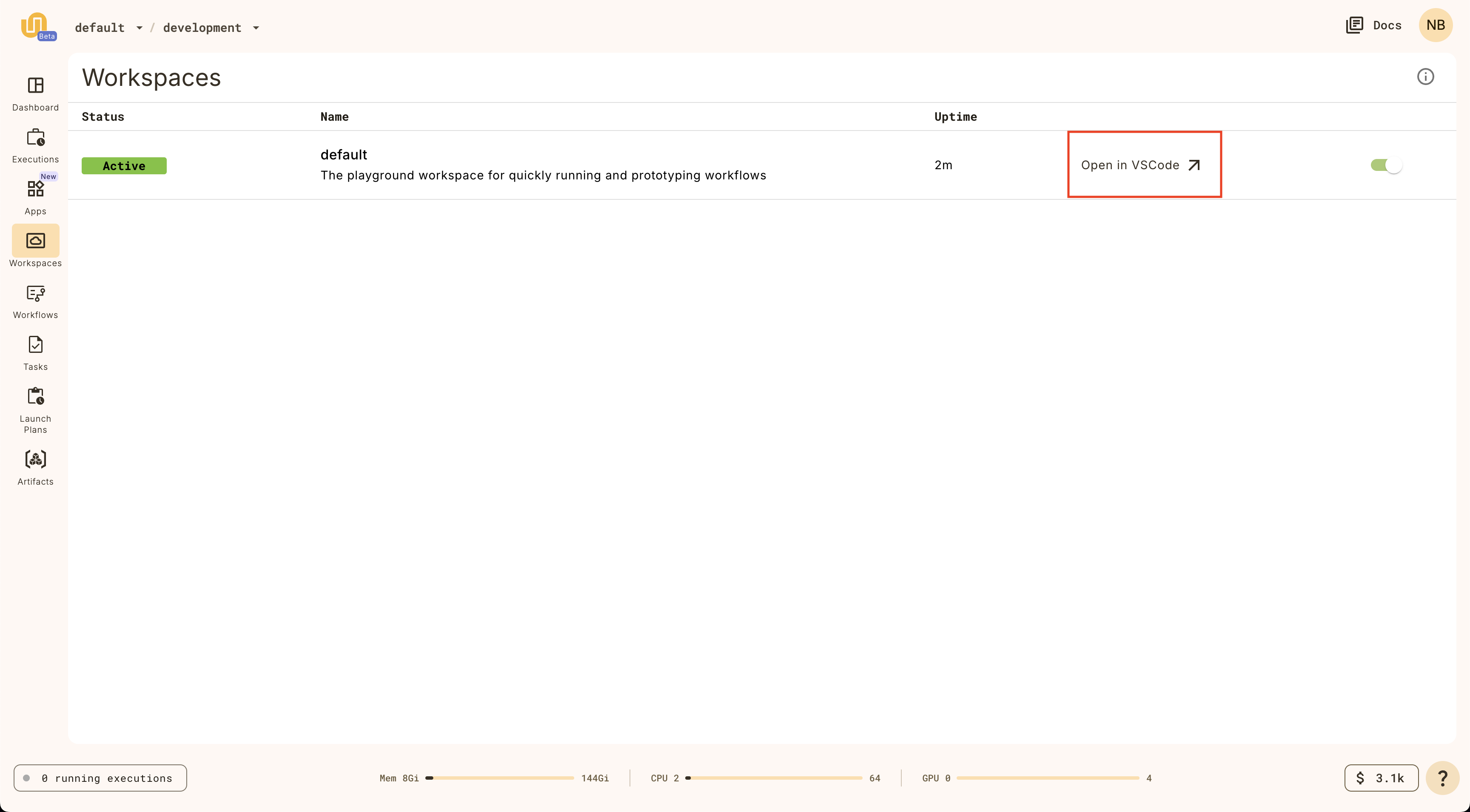

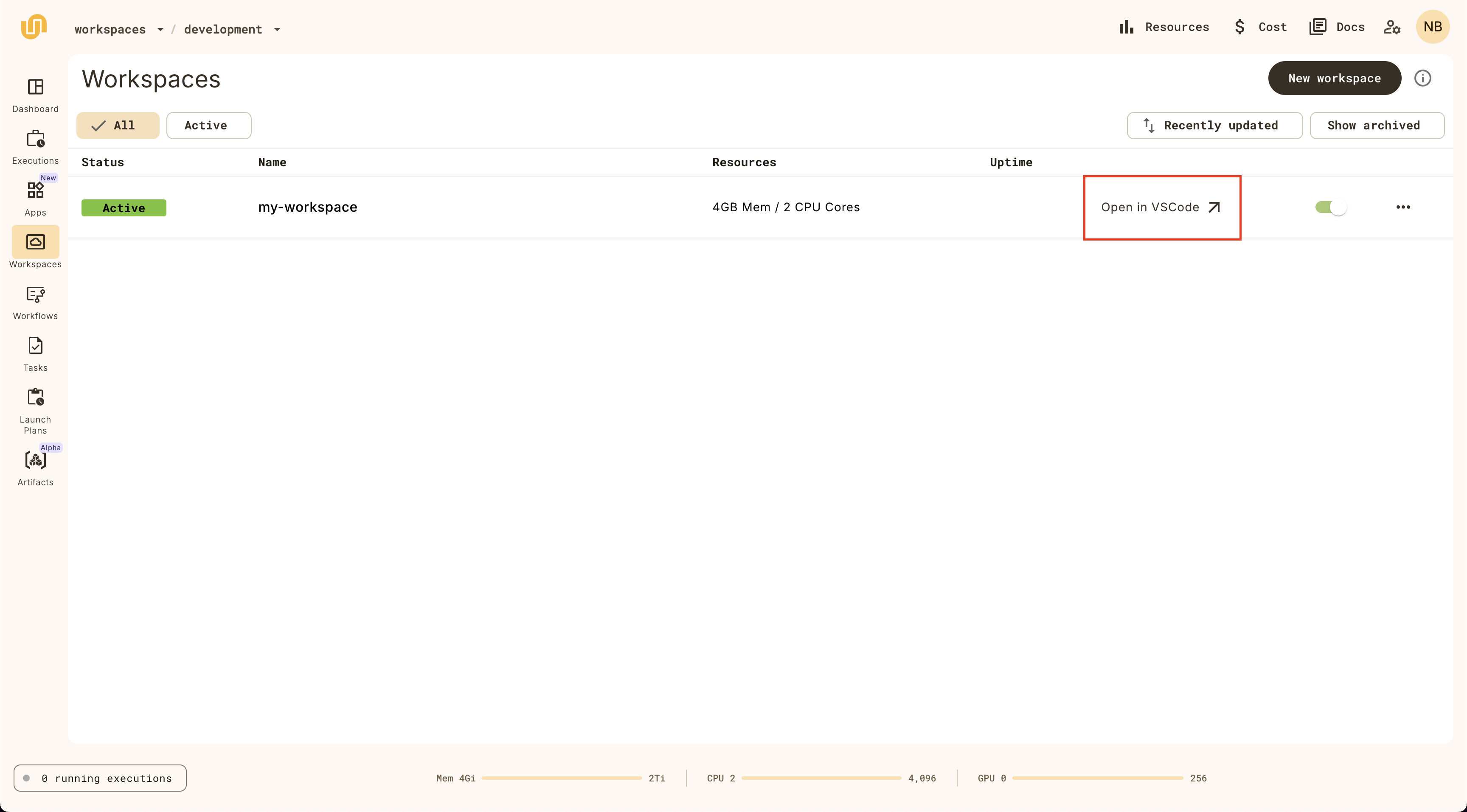

When the `Status` is `Active` on the `default` workspace, you can click on it

again to open the workspace.

_It will take a few moments to load the VSCode interface._

:::)

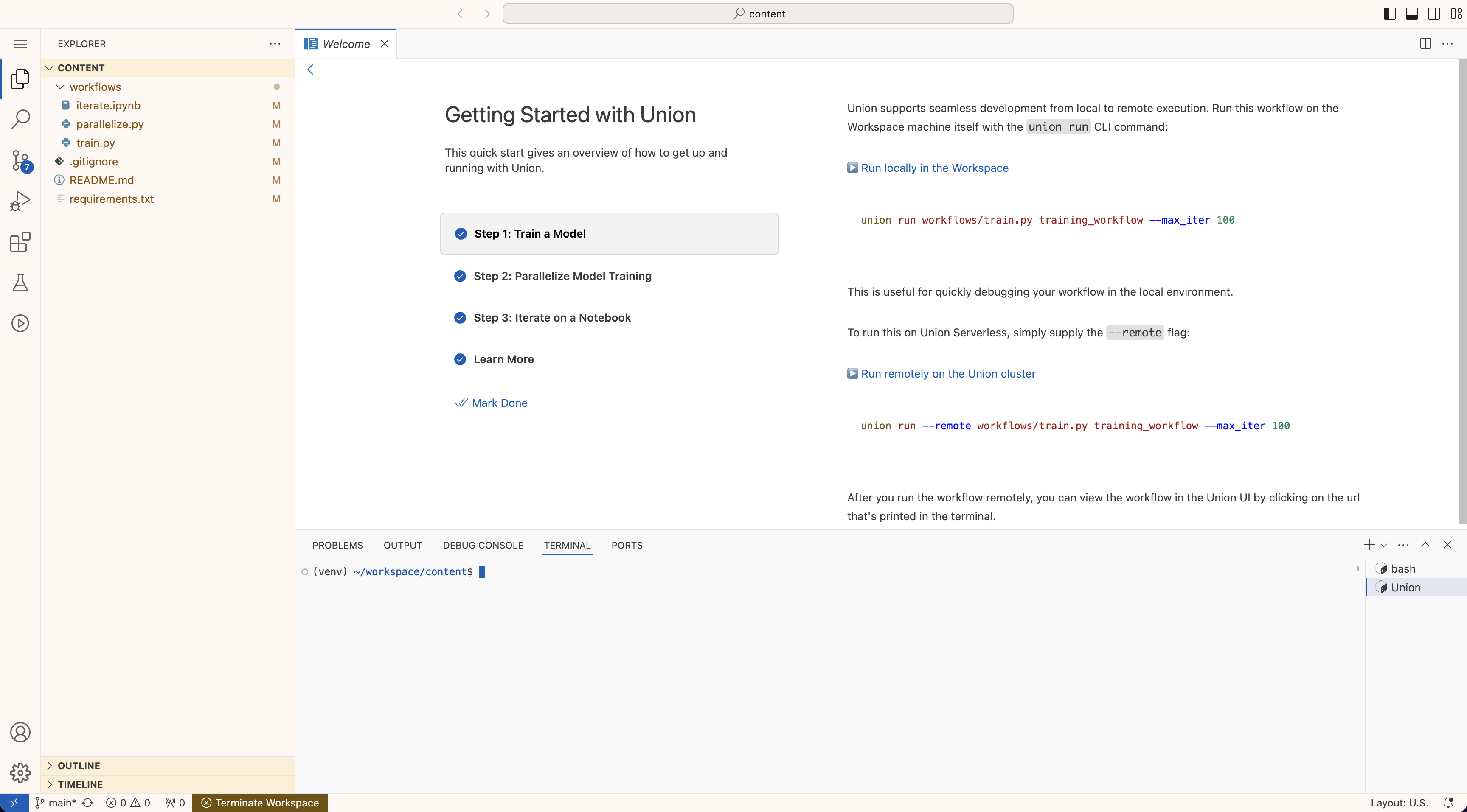

Complete walkthrough

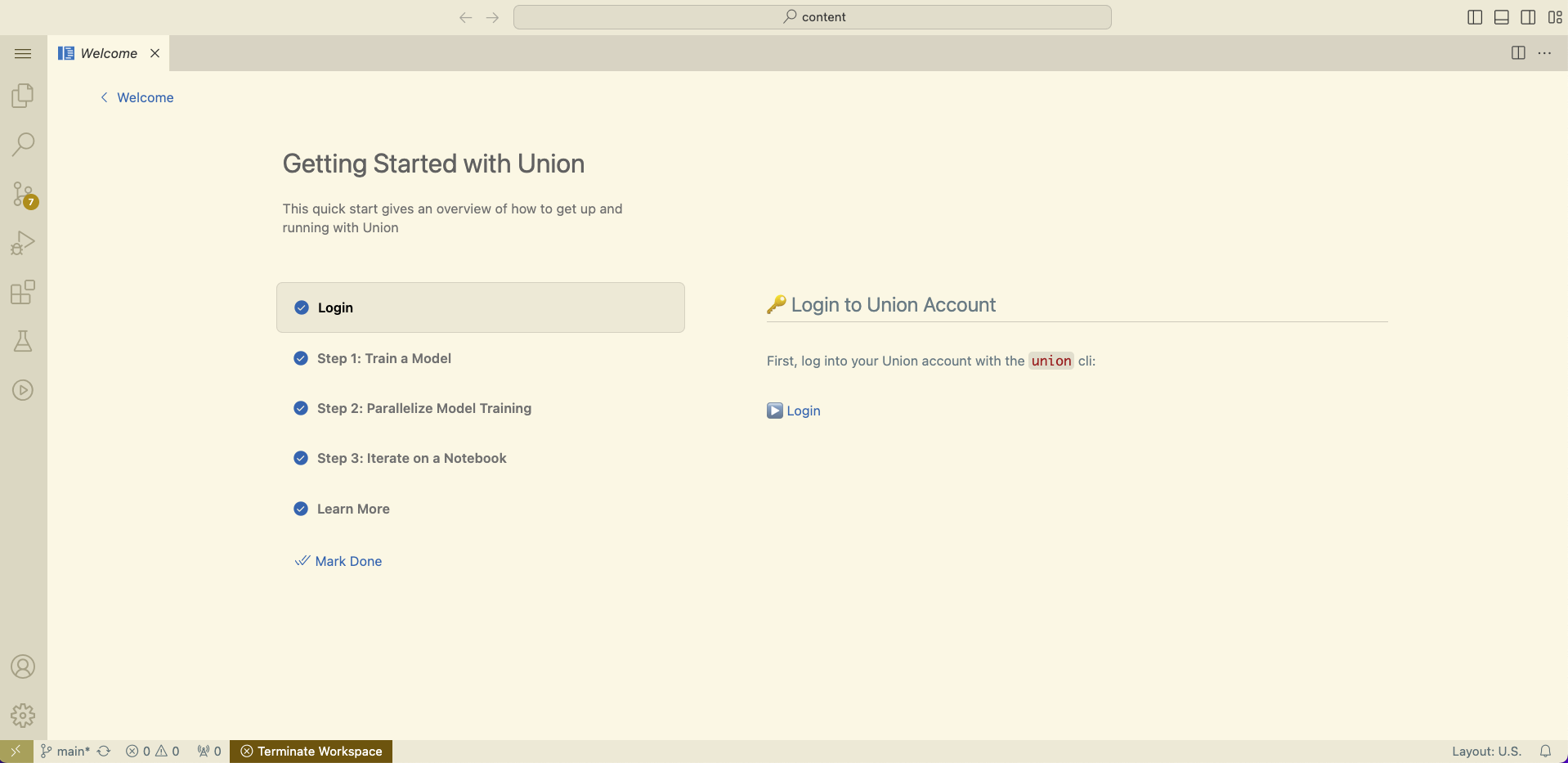

Once the workspace is open, you should see a VSCode interface in your browser.

In the walkthrough, you'll learn how to:

1. 🤖 Train a model

2. 🔀 Parallelize model training

3. 📘 Iterate on a Jupyter Notebook

Stop workspace

The workspace will terminate after 20 minutes of idle time, but you can also

stop it manually on the Workspaces page.

🎉 Congratulations! You've just run your first workflow on {{< key product_name >}}.

## Subpages

- **Getting started > Local setup**

- **Getting started > First project**

- **Getting started > Understanding the code**

- **Getting started > Running your workflow**

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/getting-started/local-setup ===

# Local setup

In [Getting started](./_index) we showed you how to run your first workflow right in the {{< key product_name >}} interface, in the browser.

In this section we will set up your local environment so that you can start building and deploying {{< key product_name >}} workflows from your local machine.

## Install `uv`

First, [install `uv`](https://docs.astral.sh/uv/#getting-started).

> [!NOTE] Using `uv` as best practice

> The `uv` tool is our [recommended package and project manager](https://docs.astral.sh/uv/).

> It replaces `pip`, `pip-tools`, `pipx`, `poetry`, `pyenv`, `twine`, `virtualenv`, and more.

>

> You can, of course, use other tools,

> but all discussion in these pages will use `uv`,

> so you will have to adapt the directions as appropriate.

## Ensure the correct version of Python is installed

{{< key kit_name >}} requires Python `>=3.9,<3.13`.

We recommend using `3.12`.

You can install it with:

```shell

$ uv python install 3.12

```

> [!NOTE] Uninstall higher versions of Python

> When installing Python packages "as tools" (as we do below with the `{{< key kit >}}`),

> `uv` will default to the latest version of Python available on your system.

> If you have a version `>=3.13` installed, you will need to uninstall it since `{{< key kit >}}` requires `>=3.9,<3.13`.

## Install the `{{< key cli >}}` CLI

Once `uv` is installed, use it to install the `{{< key cli >}}` CLI by installing the `{{< key kit >}}` Python package:

```shell

$ uv tool install {{< key kit >}}

```

This will make the `{{< key cli >}}` CLI globally available on your system.

> [!NOTE] Add the installation location to your PATH

> `uv` installs tools in `~/.local/bin` by default.

> Make sure this location is in your `PATH`, so you can run the `{{< key cli >}}` command from anywhere.

> `uv` provides a convenience command to do this: `uv tool update-shell`.

>

> Note that later in this guide we will be running the `{{< key cli >}}` CLI to run your workflows.

> In those cases you will be running `{{< key cli >}}` within the Python virtual environment of your workflow project.

> You will not be using this globally installed instance of `{{< key cli >}}`.

> This instance of `{{< key cli >}}` is only used during the configuration step, below, when no projects yet exist.

## Configure the connection to your cluster

Next, you need to create a configuration file that contains your {{< key product_name >}} connection information:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} create login --serverless

```

This will create the `~/.union/config.yaml` with the configuration information to connect to {{< key product_name >}} Serverless.

> [!NOTE] These directions apply to {{< key product_name >}} Serverless

> To configure a connection to your {{< key product_name >}} instance in {{< key product_name >}} BYOC, see the

> [BYOC version of this page](/docs/v1/byoc//user-guide/getting-started/local-setup#configure-the-connection-to-your-cluster).

> To configure a connection to your {{< key product_name >}} instance in {{< key product_name >}} Self-managed, see the

> [Self-managed version of this page](/docs/v1/selfmanaged//user-guide/getting-started/local-setup#configure-the-connection-to-your-cluster).

By default, the {{< key cli_name >}} CLI will look for a configuration file at `~/.union/config.yaml`. (See **{{< key cli_name >}} CLI** for more details.)

You can override this behavior to specify a different configuration file by setting the `{{< key config_env >}}` environment variable:

```shell

$ export {{< key config_env >}}=~/.my-config-location/my-config.yaml

```

Alternatively, you can always specify the configuration file on the command line when invoking `{{< key cli >}}` by using the `--config` flag.

For example:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} --config ~/.my-config-location/my-config.yaml run my_script.py my_workflow

```

> [!WARNING]

> If you have previously used {{< key product_name >}}, you may have configuration files left over that will interfere with

> access to {{< key product_name >}} Serverless through the {{< key cli_name >}} CLI tool.

> Make sure to remove any files in `~/.unionai/` or `~/.union/` and unset the environment

> variables `UNIONAI_CONFIG` and `UNION_CONFIG` to avoid conflicts.

See **Development cycle > Running in a local cluster** for more details on

the format of the `yaml` file.

## Check your CLI configuration

To check your CLI configuration, run:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} info

```

You should get a response like this:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} info

╭────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── {{< key product_name >}} CLI Info ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ │

│ {{< key cli >}} is the CLI to interact with {{< key product_name >}}. Use the CLI to register, create and track task and workflow executions locally and remotely. │

│ │

│ {{< key product_name >}} Version : 0.1.132 │

│ Flytekit Version : 1.14.3 │

│ {{< key product_name >}} Endpoint : serverless-1.us-east-2.s.union.ai │

│ Config Source : file │

│ │

╰───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

```

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/getting-started/first-project ===

# First project

In this section we will set up a new project.

This involves creating a local project directory holding your project code

and a corresponding {{< key product_name >}} project to which you will deploy that code using the `{{< key cli >}}` CLI.

## Create a new {{< key product_name >}} project

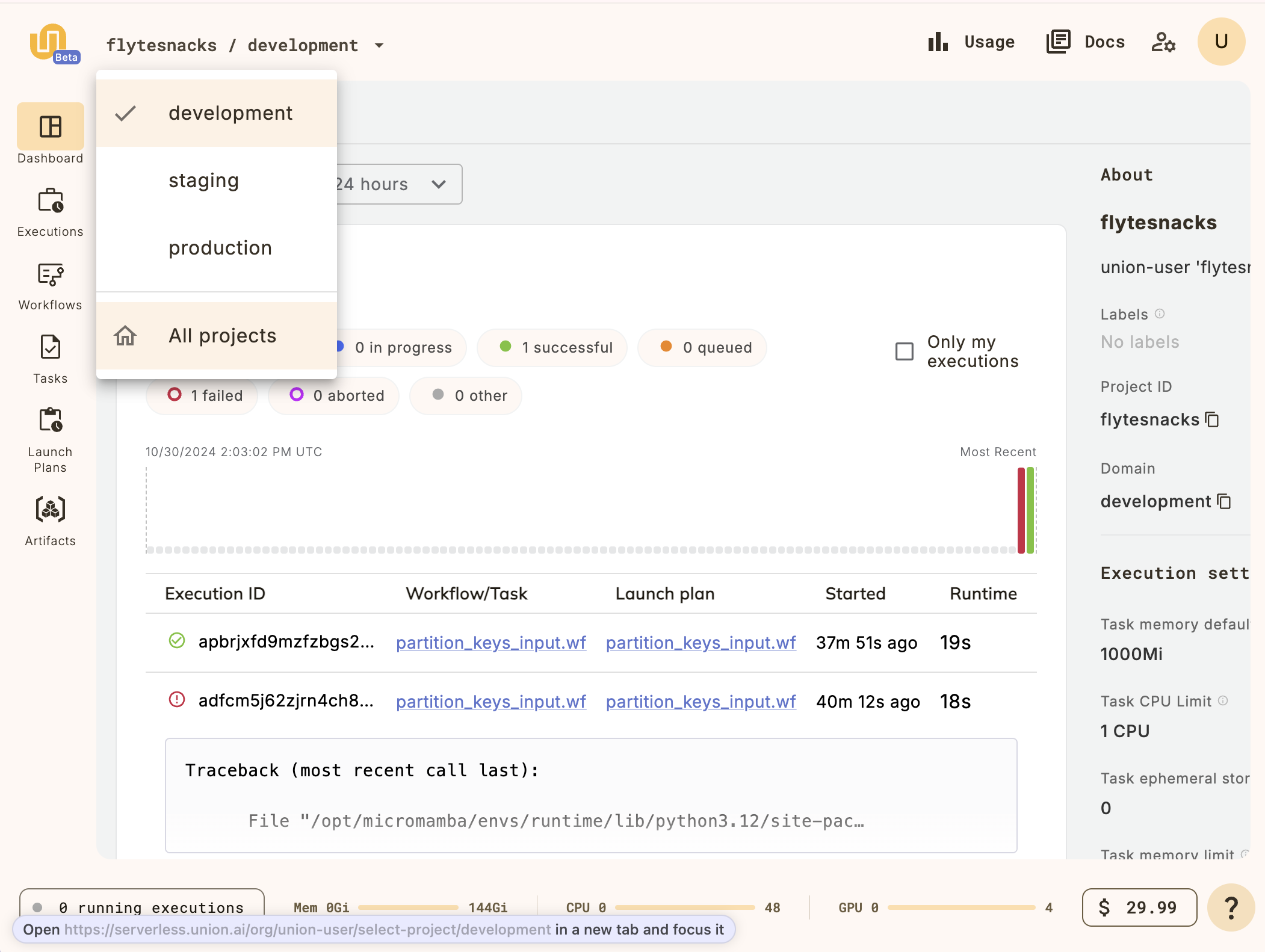

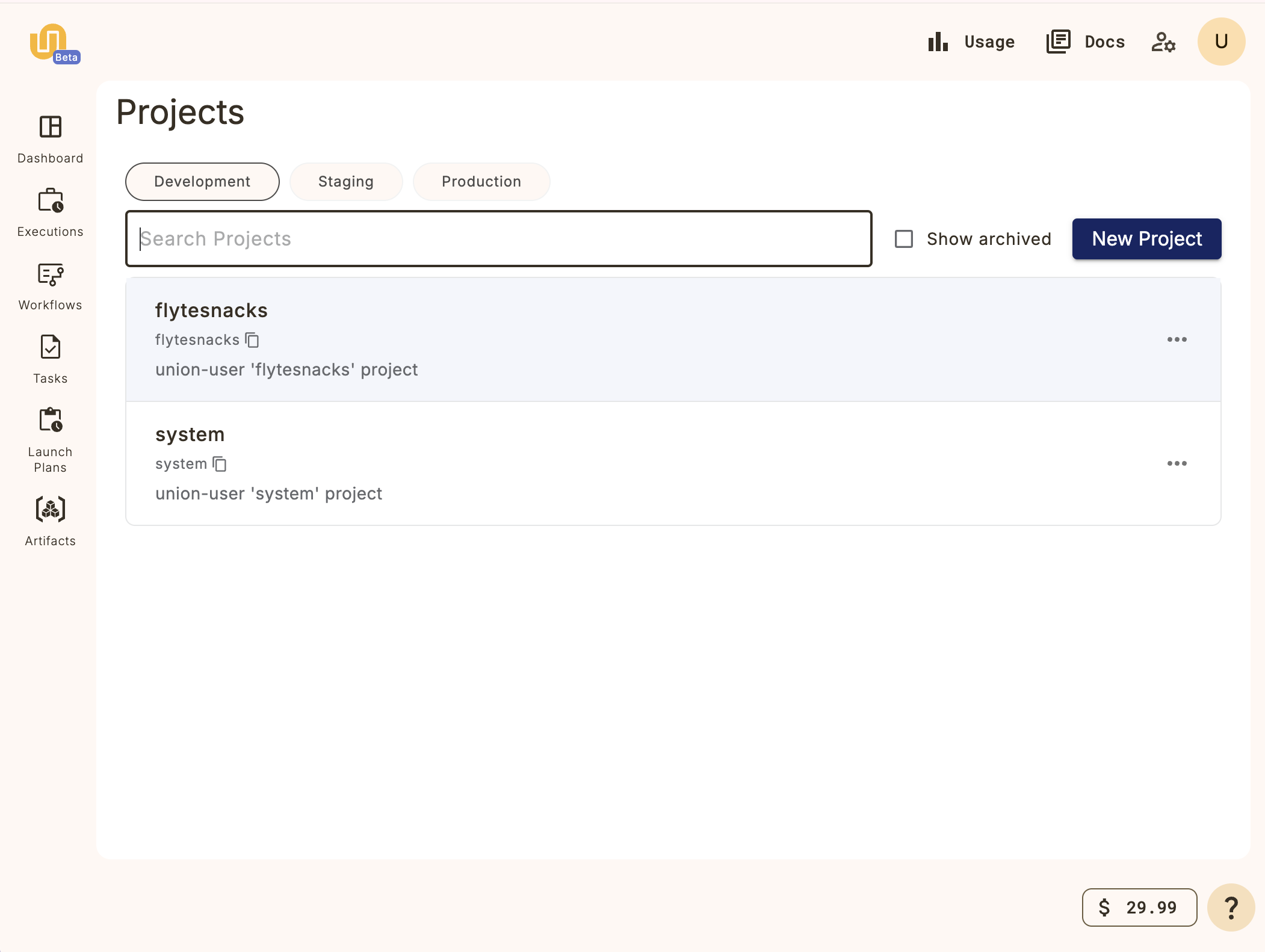

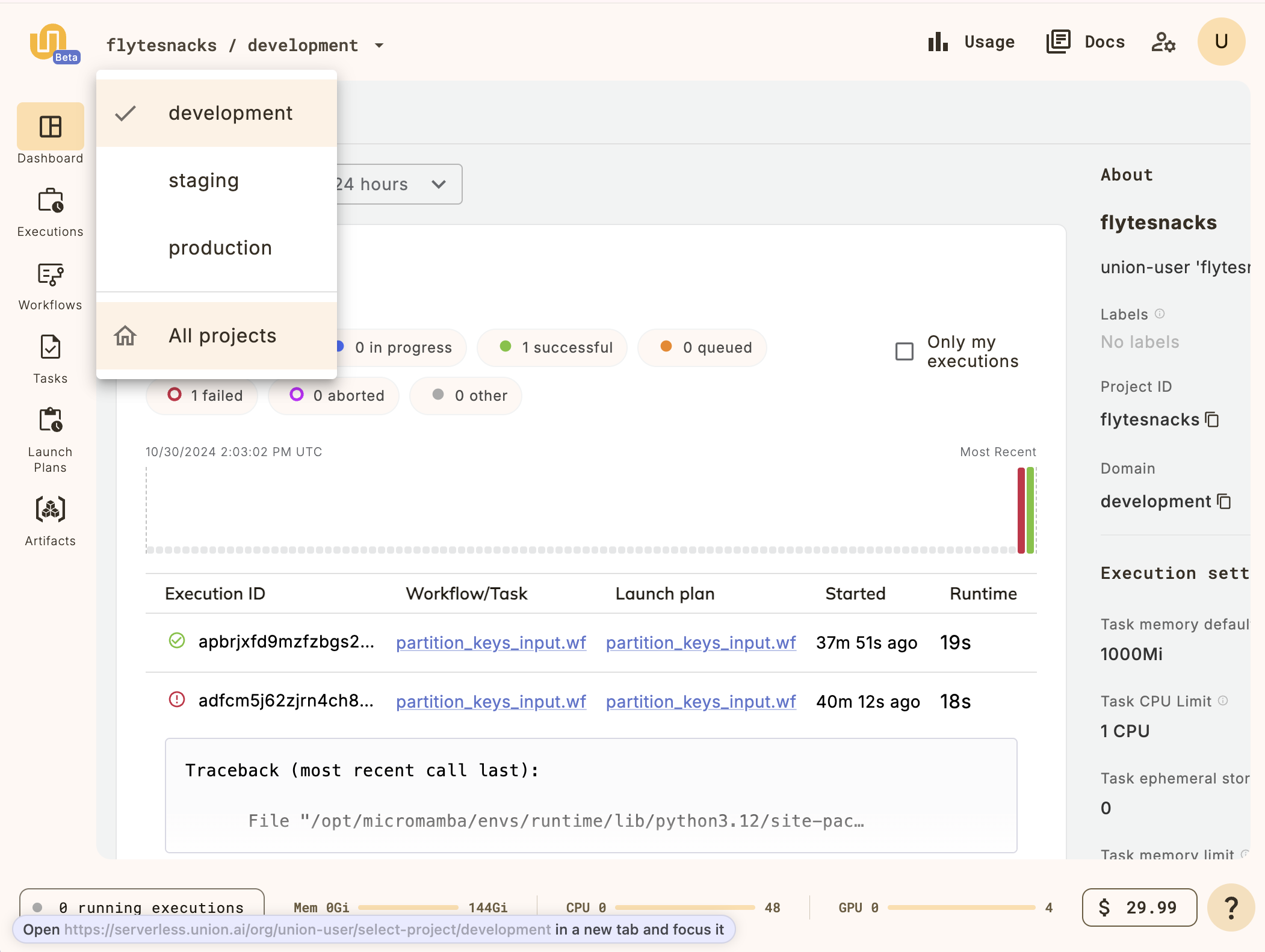

Create a new project in the {{< key product_name >}} UI by clicking on the project breadcrumb at the top left and selecting **All projects**:

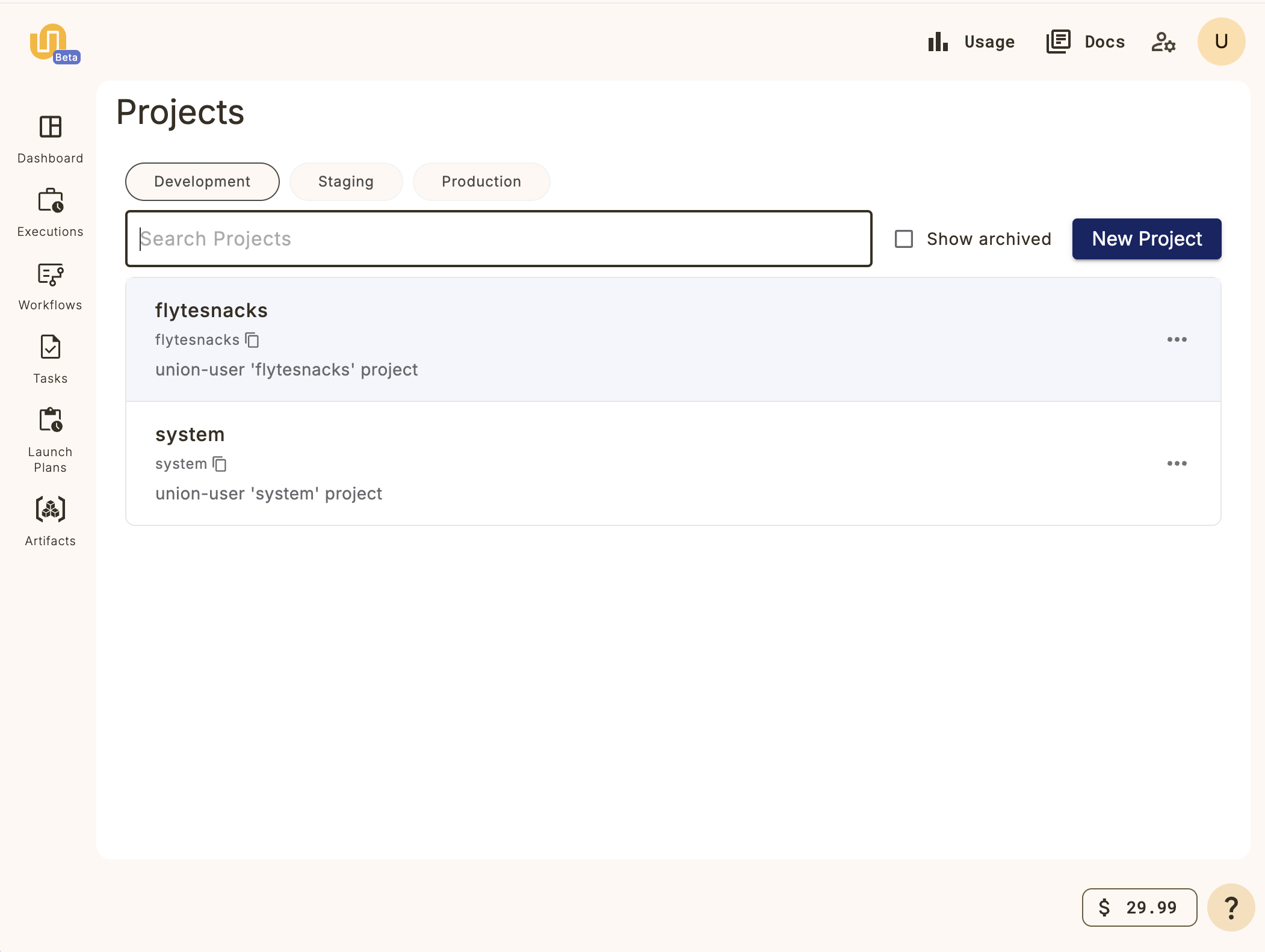

This will take you to the **Projects list**:

Click on the **New Project** button and fill in the details for your new project.

For this example, let's create a project called **My project**:

You now have a project on {{< key product_name >}} named "My Project" (and with project ID `my-project`) into which you can register your workflows.

> [!NOTE] Default project

> {{< key product_name >}} provides a default project (called **{{< key default_project >}}**) where all your workflows will be registered unless you specify otherwise.

> In this section, however, we will be using the project we just created, not the default.

## Initialize a local project

We will use the `{{< key cli >}} init` command to initialize a new local project corresponding to the project created on your {{< key product_name >}} instance:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} init --template {{< key product >}}-simple my-project

```

The resulting directory will look like this:

```shell

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── hello_world.py

├── pyproject.toml

└── uv.lock

```

> [!NOTE] Local project directory name same as {{< key product_name >}} project ID

> It is good practice to name your local project directory the same as your

> {{< key product_name >}} project ID, as we have done here.

Next, let's look at the contents of the local project directory.

Continue to **Getting started > Understanding the code**.

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/getting-started/understanding-the-code ===

# Understanding the code

This is a simple "Hello, world!" example consisting of flat directory:

```shell

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── hello_world.py

├── pyproject.toml

└── uv.lock

```

## Python code

The `hello_world.py` file illustrates the essential components of a {{< key product_name >}} workflow:

```python

# Hello World

import union

image_spec = union.ImageSpec(

# The name of the image. This image will be used byt he say_hello task

name="say-hello-image",

# Lock file with dependencies to install in image

requirements="uv.lock",

# Build the image using Union's built-in cloud builder (not locally on your machine)

builder="union",

)

@union.task(container_image=image_spec)

def say_hello(name: str) -> str:

return f"Hello, {name}!"

@union.workflow

def hello_world_wf(name: str = "world") -> str:

greeting = say_hello(name=name)

return greeting

```

### ImageSpec

The `ImageSpec` object is used to define the container image that will run the tasks in the workflow.

Here we have the simplest possible `ImageSpec` object, which specifies:

* The `name` of the image.

* This name will be used to identify the image in the container registry.

* The `requirements` parameter.

* We specify that the requirements should be read from the `uv.lock` file.

* The `builder` to use to build the image.

* We specify `union` to indicate that the image is built using {{< key product_name >}}'s cloud image builder.

See **Development cycle > ImageSpec** for more information.

### Tasks

The `@{{< key kit_as >}}.task` decorator indicates a Python function that defines a **Core concepts > Tasks**.

A task tasks some input and produces an output.

When deployed to {{< key product_name >}} cluster, each task runs in its own Kubernetes pod.

For a full list of task parameters, see **Core concepts > Tasks > Task parameters**.

### Workflow

The `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` decorator indicates a function that defines a **Core concepts > Workflows**.

This function contains references to the tasks defined elsewhere in the code.

A workflow appears to be a Python function but is actually a [DSL](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domain-specific_language) that only supports a subset of Python syntax and semantics.

When deployed to {{< key product_name >}}, the workflow function is compiled to construct the directed acyclic graph (DAG) of tasks, defining the order of execution of task pods and the data flow dependencies between them.

> [!NOTE] `@{{< key kit_as >}}.task` and `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` syntax

> * The `@{{< key kit_as >}}.task` and `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` decorators will only work on functions at the top-level

> scope of the module.

> * You can invoke tasks and workflows as regular Python functions and even import and use them in

> other Python modules or scripts.

> * Task and workflow function signatures must be type-annotated with Python type hints.

> * Task and workflow functions must be invoked with keyword arguments.

## pyproject.toml

The `pyproject.toml` is the standard project configuration used by `uv`.

It specifies the project dependencies and the Python version to use.

The default `pyproject.toml` file created by `{{< key cli >}} init` from the `{{< key product >}}-simple` template looks like this

```toml

[project]

name = "{{< key product >}}-simple"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "A simple {{< key product_name >}} project"

readme = "README.md"

requires-python = ">=3.9,<3.13"

dependencies = ["{{< key kit >}}"]

```

(You can update the `name` and `description` to match the actual name of your project, `my-project`, if you like).

The most important part of the file is the list of dependencies, in this case consisting of only one package, `{{< key kit >}}`.

See [uv > Configuration > Configuration files](https://docs.astral.sh/uv/configuration/files/) for details.

## uv.lock

The `uv.lock` file is generated from `pyproject.toml` by `uv sync` command.

It contains the exact versions of the dependencies required by the project.

The `uv.lock` included in the `init` template may not reflect the latest version of the dependencies, so you should update it by doing a fresh `uv sync`.

See [uv > Concepts > Projects > Locking and syncing](https://docs.astral.sh/uv/concepts/projects/sync/) for details.

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/getting-started/running-your-workflow ===

# Running your workflow

## Python virtual environment

The first step is to ensure that your `uv.lock` file is properly generated from your `pyproject.toml` file and that your local Python virtual environment is properly set up.

Using `uv`, you can install the dependencies with the command:

```shell

$ uv sync

```

You can then activate the virtual environment with:

```shell

$ source .venv/bin/activate

```

> [!NOTE] `activate` vs `uv run`

> When running the `{{< key cli >}}` CLI within your local project you must run it in the virtual

> environment _associated with_ that project.

> This differs from our earlier usage of the tool when

> **Getting started > Running your workflow > we installed `{{< key cli >}}` globally** in order to

> **Getting started > Running your workflow > set up its configuration**.

>

> To run `{{< key cli >}}` within your project's virtual environment using `uv`,

> you can prefix it use the `uv run` command. For example:

>

> `uv run {{< key cli >}} ...`

>

> Alternatively, you can activate the virtual environment with `source .venv/bin/activate` and then

> run the `{{< key cli >}}` command directly.

>

> In our examples we assume that you are doing the latter.

## Run the code locally

Because tasks and workflows are defined as regular Python functions, they can be executed in your local Python environment.

You can run the workflow locally with the command **Union CLI > `union` CLI commands**:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} run hello_world.py hello_world_wf

```

You should see output like this:

```shell

Running Execution on local.

Hello, world!

```

You can also pass in parameters to the workflow (assuming they declared in the workflow function):

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} run hello_world.py hello_world_wf --name="everybody"

```

You should see output like this:

```shell

Running Execution on local.

Hello, everybody!

```

## Running remotely on {{< key product_name >}} in the cloud

Running you code in your local Python environment is useful for testing and debugging.

But to run them at scale, you will need to deploy them (or as we say, "register" them) on to your {{< key product_name >}} instance in the cloud.

When task and workflow code is registered:

* The `@{{< key kit_as >}}.task` function is loaded into a container defined by the `ImageSpec` object specified in the `container_image` parameter of the decorator.

* The `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` function is compiled into a directed acyclic graph that controls the running of the tasks invoked within it.

To run the workflow on {{< key product_name >}} in the cloud, use the **Union CLI > `union` CLI commands** and the

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} run --remote --project my-project --domain development hello_world.py hello_world_wf

```

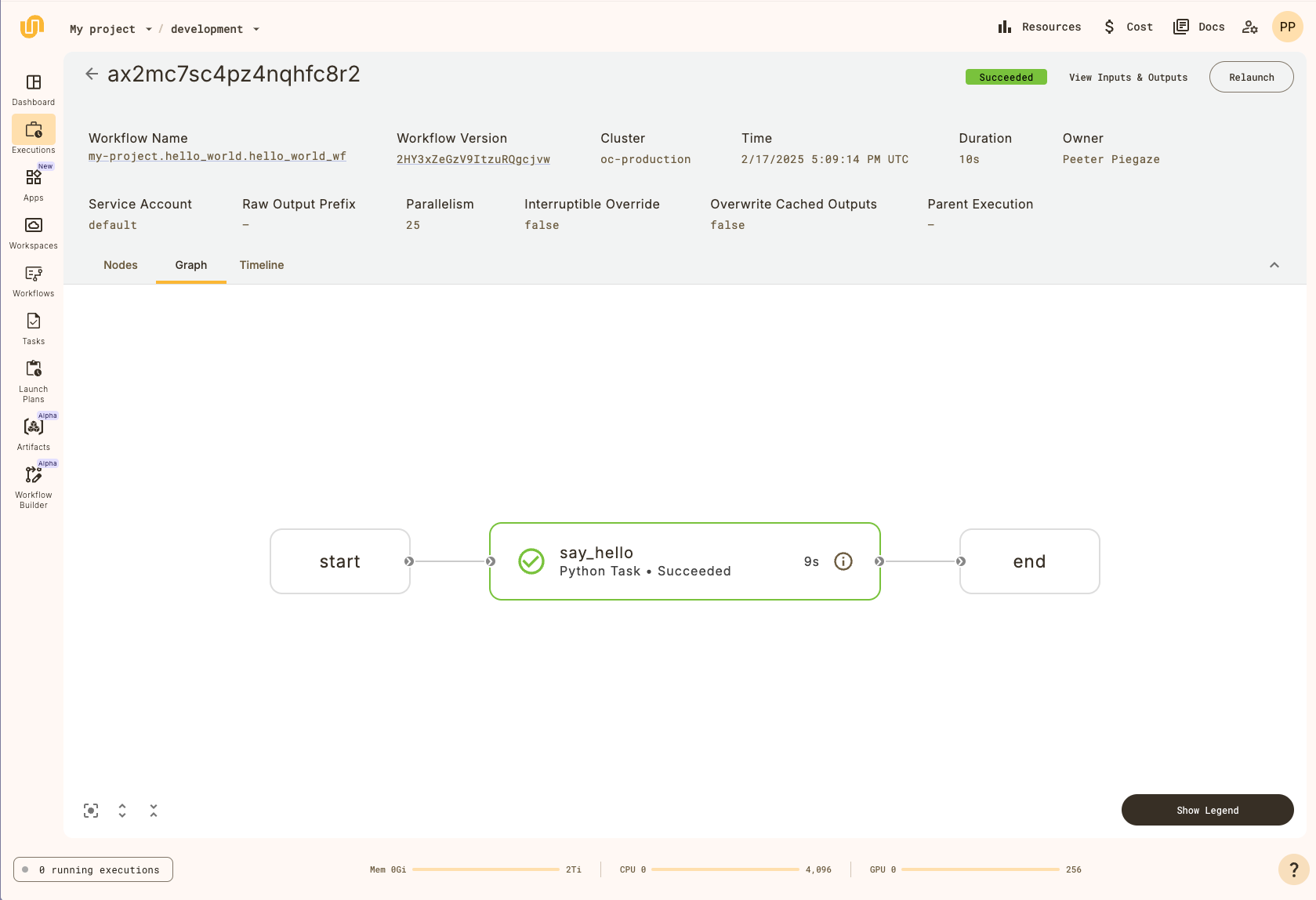

The output displays a URL that links to the workflow execution in the UI:

```shell

👍 Build submitted!

⏳ Waiting for build to finish at: https://serverless.union.ai/org/...

✅ Build completed in 0:01:57!

[✔] Go to https://serverless.union.ai/org/... to see execution in the UI.

```

Click the link to see the execution in the UI.

## Register the workflow without running

Above we used the `{{< key cli >}} run --remote` to register and immediately run a workflow on {{< key product_name >}}.

This is useful for quick testing, but for more complex workflows you may want to register the workflow first and then run it from the {{< key product_name >}} interface.

To do this, you can use the `{{< key cli >}} register` command to register the workflow code with {{< key product_name >}}.

The form of the command is:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} register []

```

in our case, from within the `getting-started` directory, you would do:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} register --project my-project --domain development .

```

This registers all code in the current directory to {{< key product_name >}} but does not immediately run anything.

You should see the following output (or similar) in your terminal:

```shell

Running {{< key cli >}} register from /Users/my-user/scratch/my-project with images ImageConfig(default*image=Image(name='default', fqn='cr.flyte.org/flyteorg/flytekit', tag='py3.12-1.14.6', digest=None), images=[Image(name='default', fqn='cr.flyte.org/flyteorg/flytekit', tag='py3.12-1.14.6', digest=None)]) and image destination folder /root on 1 package(s) ('/Users/my-user/scratch/my-project',)

Registering against demo.hosted.unionai.cloud

Detected Root /Users/my-user/my-project, using this to create deployable package...

Loading packages ['my-project'] under source root /Users/my-user/my-project

No output path provided, using a temporary directory at /var/folders/vn/72xlcb5d5jbbb3kk_q71sqww0000gn/T/tmphdu9wf6* instead

Computed version is sSFSdBXwUmM98sYv930bSQ

Image say-hello-image:lIpeqcBrlB8DlBq0NEMR3g found. Skip building.

Serializing and registering 3 flyte entities

[✔] Task: my-project.hello_world.say_hello

[✔] Workflow: my-project.hello_world.hello_world_wf

[✔] Launch Plan: my-project.hello_world.hello_world_wf

Successfully registered 3 entities

```

## Run the workflow from the {{< key product_name >}} interface

To run the workflow, you need to go to the {{< key product_name >}} interface:

1. Navigate to the {{< key product_name >}} dashboard.

2. In the left sidebar, click **Workflows**.

3. Search for your workflow, then select the workflow from the search results.

4. On the workflow page, click **Launch Workflow**.

5. In the "Create New Execution" dialog, you can change the workflow version, launch plan, and inputs (if present). Click "Advanced options" to change the security context, labels, annotations, max parallelism, override the interruptible flag, and overwrite cached inputs.

6. To execute the workflow, click **Launch**. You should see the workflow status change to "Running", then "Succeeded" as the execution progresses.

To view the workflow execution graph, click the **Graph** tab above the running workflow.

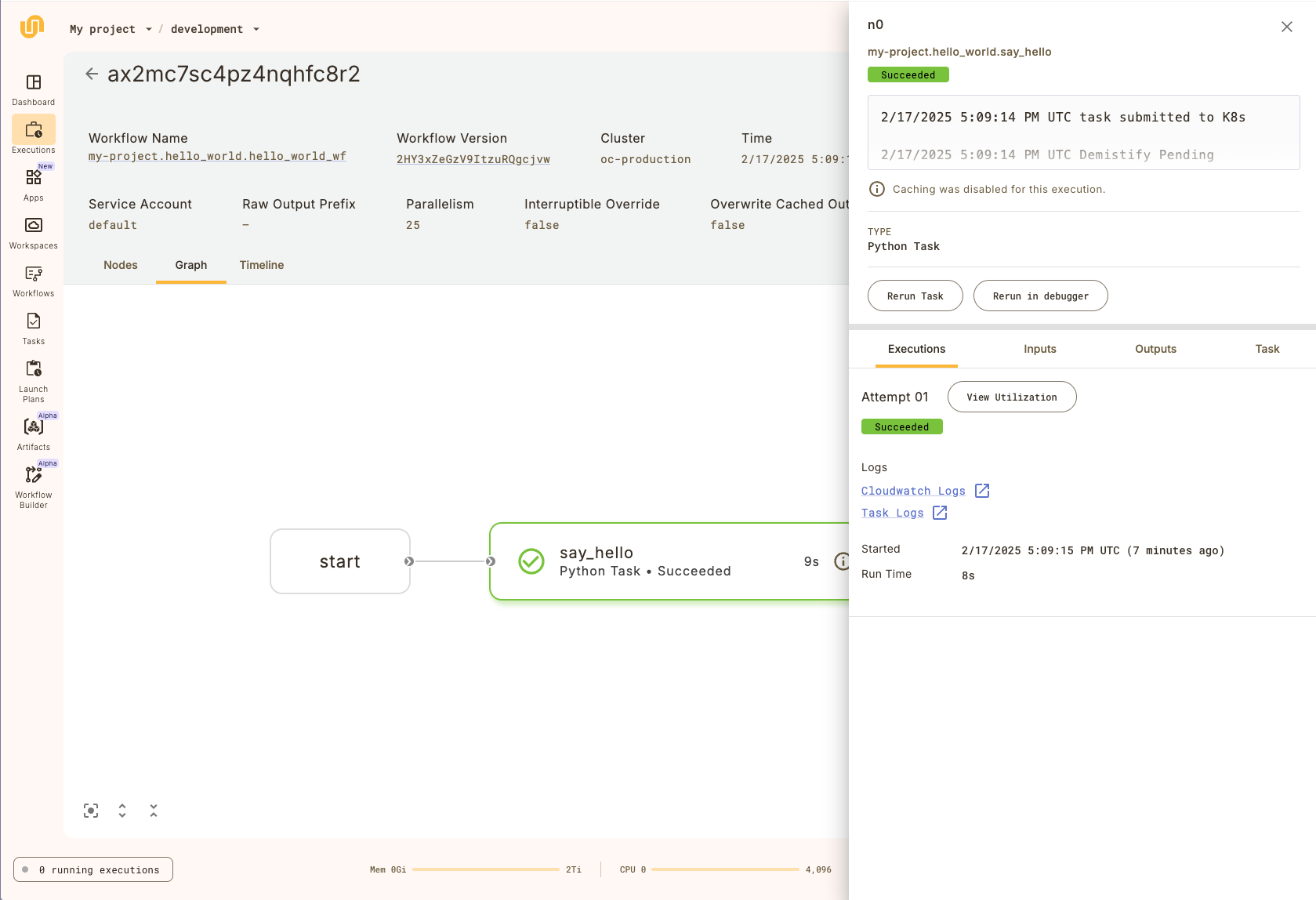

## View the workflow execution on {{< key product_name >}}

When you view the workflow execution graph, you will see the following:

Above the graph, there is metadata that describes the workflow execution, such as the

duration and the workflow version. Next, click on the `evaluate_model` node to open up a

sidebar that contains additional information about the task:

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts ===

# Core concepts

{{< key product_name >}} is a platform for building and orchestrating the execution of interconnected software processes across machines in a computer cluster.

In {{< key product_name >}} terminology, the software processes are called *tasks* and the overall organization of connections between tasks is called a *workflow*.

The tasks in a workflow are connected to each other by their inputs and outputs. The output of one task becomes the input of another.

More precisely, a workflow in {{< key product_name >}} is a *directed acyclic graph (DAG)* of *nodes* where each node is a unit of execution and the edges between nodes represent the flow of data between them.

The most common type of node is a task node (which encapsulates a task), though there are also workflow nodes (which encapsulate subworkflows) and branch nodes.

In most contexts we just say that a workflow is a DAG of tasks.

You define tasks and workflows in Python using the {{< key kit_name >}} SDK. The {{< key kit_name >}} SDK provides a set of decorators and classes that allow you to define tasks and workflows in a way that is easy to understand and work with.

Once defined, tasks and workflows are deployed to your {{< key product_name >}} instance (we say they are *registered* to the instance), where they are compiled into a form that can be executed on your {{< key product_name >}} cluster.

In addition to tasks and workflows, another important concept in {{< key product_name >}} is the **Core concepts > Launch plans**.

A launch plan is like a template that can be used to define the inputs to a workflow.

Triggering a launch plan will launch its associated workflow with the specified parameters.

## Defining tasks and workflows

Using the {{< key kit_name >}} SDK, tasks and workflows are defined as Python functions using the `@{{< key kit_as >}}.task` and `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` decorators, respectively:

```python

import {{< key kit_import >}}

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def task_1(a: int, b: int, c: int) -> int:

return a + b + c

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def task_2(m: int, n: int) -> int:

return m * n

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def task_3(x: int, y: int) -> int:

return x - y

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def my_workflow(a: int, b: int, c: int, m: int, n: int) -> int:

x = task_1(a=a, b=b, c=c)

y = task_2(m=m, n=n)

return task_3(x=x, y=y)

```

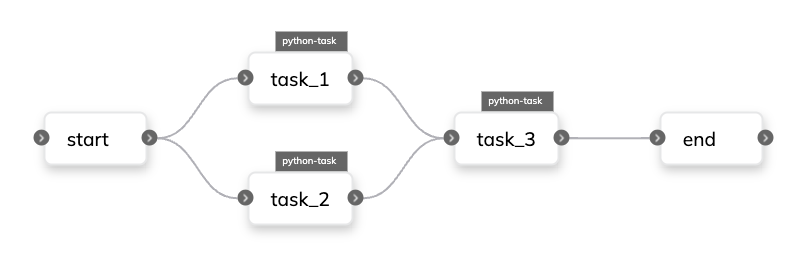

Here we see three tasks defined using the `@{{< key kit_as >}}.task` decorator and a workflow defined using the `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` decorator.

The workflow calls `task_1` and `task_2` and passes the results to `task_3` before finally outputting the result of `task_3`.

When the workflow is registered, {{< key product_name >}} compiles the workflow into a directed acyclic graph (DAG) based on the input/output dependencies between the tasks.

The DAG is then used to execute the tasks in the correct order, taking advantage of any parallelism that is possible.

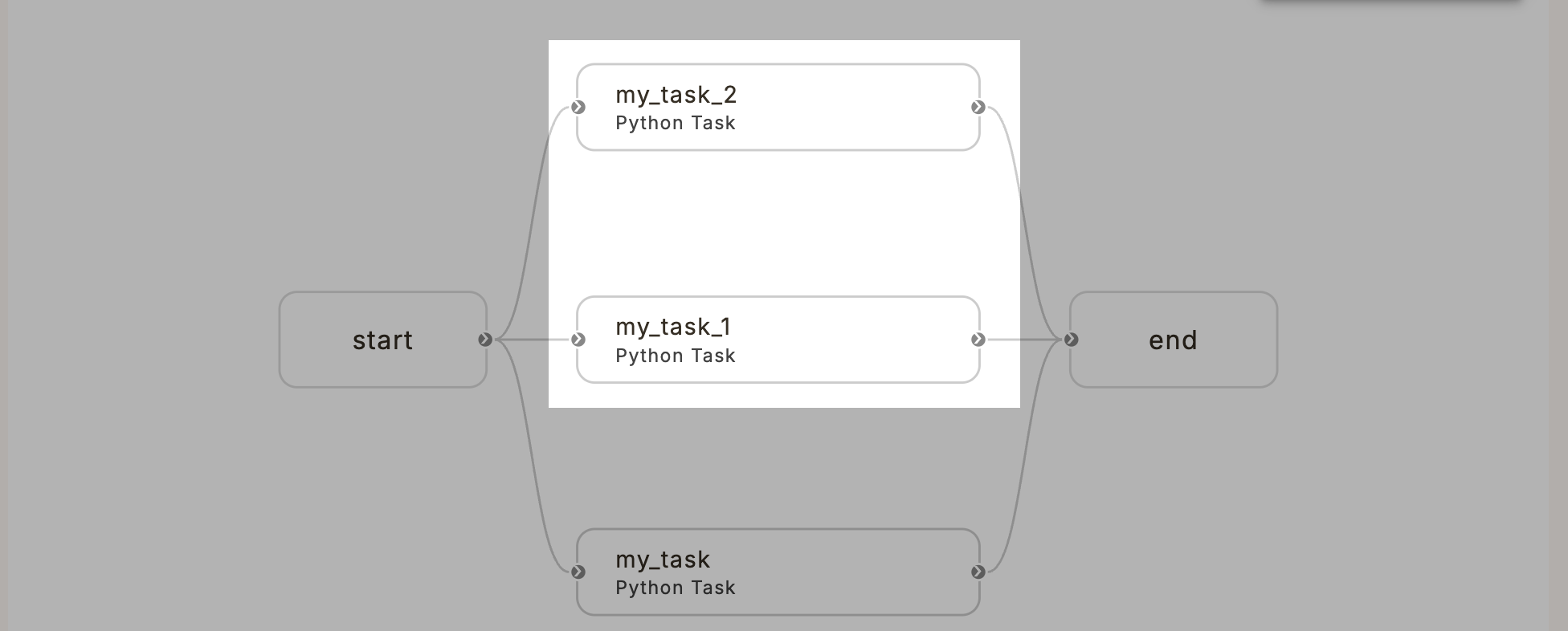

For example, the workflow above results in the following DAG:

### Type annotation is required

One important difference between {{< key product_name >}} and generic Python is that in {{< key product_name >}} all inputs and outputs *must be type annotated*.

This is because tasks are strongly typed, meaning that the types of the inputs and outputs are validated at deployment time.

See **Core concepts > Tasks > Tasks are strongly typed** for more details.

### Workflows *are not* full Python functions

The definition of a workflow must be a valid Python function, so it can be run locally as a normal Python function during development,

but only *a subset of Python syntax is allowed*, because it must also be compiled into a DAG that is deployed and executed on {{< key product_name >}}.

*Technically then, the language of a workflow function is a domain-specific language (DSL) that is a subset of Python.*

See **Core concepts > Workflows** for more details.

## Registering tasks and workflows

### Registering on the command line with `{{< key cli >}}` or `{{< key ctl >}}`

In most cases, workflows and tasks (and possibly other things, such as launch plans) are defined in your project code and registered as a bundle using `{{< key cli >}}` or `{{< key ctl >}}` For example:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} register ./workflows --project my_project --domain development

```

Tasks can also be registered individually, but it is more common to register alongside the workflow that uses them.

See **Development cycle > Running your code**.

### Registering in Python with `{{< key kit_remote >}}`

As with all {{< key product_name >}} command line actions, you can also perform registration of workflows and tasks programmatically with [`{{< key kit_remote >}}`](), specifically, [`{{< key kit_remote >}}.register_script`](),

[`{{< key kit_remote >}}.register_workflow`](), and

[`{{< key kit_remote >}}.register_task`]().

## Results of registration

When the code above is registered to {{< key product_name >}}, it results in the creation of five objects:

* The tasks `workflows.my_example.task_1`, `workflows.my_example.task_2`, and `workflows.my_example.task_3` (see **Core concepts > Tasks** for more details).

* The workflow `workflows.my_example.my_workflow`.

* The default launch plan `workflows.my_example.my_workflow` (see **Core concepts > Launch plans** for more details).

Notice that the task and workflow names are derived from the path, file name and function name of the Python code that defines them: `..`.

The default launch plan for a workflow always has the same name as its workflow.

## Changing tasks and workflows

Tasks and workflows are changed by altering their definition in code and re-registering.

When a task or workflow with the same project, domain, and name as a preexisting one is re-registered, a new version of that entity is created.

## Inspecting tasks and workflows

### Inspecting workflows in the UI

Select **Workflows** in the sidebar to display a list of all the registered workflows in the project and domain.

You can search the workflows by name.

Click on a workflow in the list to see the **workflow view**.

The sections in this view are as follows:

* **Recent Workflow Versions**: A list of recent versions of this workflow.

Select a version to see the **Workflow version view**.

This view shows the DAG and a list of all version of the task.

You can switch between versions with the radio buttons.

* **All Executions in the Workflow**: A list of all executions of this workflow.

Click on an execution to go to the **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflow executions**.

* **Launch Workflow button**: In the top right of the workflow view, you can click the **Launch Workflow** button to run the workflow with the default inputs.

### Inspecting tasks in the UI

Select **Tasks** in the sidebar to display a list of all the registered tasks in the project and domain.

You can search the launch plans by name.

To filter for only those that are archived, check the **Show Only Archived Tasks** box.

Click on a task in the list to see the task view

The sections in the task view are as follows:

* **Inputs & Outputs**: The name and type of each input and output for the latest version of this task.

* **Recent Task Versions**: A list of recent versions of this task.

Select a version to see the **Task version view**:

This view shows the task details and a list of all version of the task.

You can switch between versions with the radio buttons.

See **Core concepts > Tasks** for more information.

* **All Executions in the Task**: A list of all executions of this task.

Click on an execution to go to the execution view.

* **Launch Task button**: In the top right of the task view, you can click the **Launch Task** button to run the task with the default inputs.

### Inspecting workflows on the command line with `{{< key ctl >}}`

To view all tasks within a project and domain:

```shell

$ {{< key ctl >}} get workflows \

--project \

--domain

```

To view a specific workflow:

```shell

$ {{< key ctl >}} get workflow \

--project \

--domain \

```

See **Uctl CLI** for more details.

### Inspecting tasks on the command line with `{{< key ctl >}}`

To view all tasks within a project and domain:

```shell

$ {{< key ctl >}} get tasks \

--project \

--domain

```

To view a specific task:

```shell

$ {{< key ctl >}} get task \

--project \

--domain \

```

See **Uctl CLI** for more details.

### Inspecting tasks and workflows in Python with `{{< key kit_remote >}}`

Use the method [`{{< key kit_remote >}}.fetch_workflow`]() or [`{{< key kit_remote >}}.client.get_workflow`]() to get a workflow.

See [`{{< key kit_remote >}}`]() for more options and details.

Use the method [`{{< key kit_remote >}}.fetch_task`]() or [`{{< key kit_remote >}}.client.get_task`]() to get a task.

See [`{{< key kit_remote >}}`]() for more options and details.

## Running tasks and workflows

### Running a task or workflow in the UI

To run a workflow in the UI, click the **Launch Workflow** button in the workflow view.

You can also run individual tasks in the UI by clicking the **Launch Task** button in the task view.

### Running a task or workflow locally on the command line with `{{< key cli >}}` or `python`

You can execute a {{< key product_name >}} workflow or task locally simply by calling it just like any regular Python function.

For example, you can add the following to the above code:

```python

if __name__ == "__main__":

my_workflow(a=1, b=2, c=3, m=4, n=5)

```

If the file is saved as `my_example.py`, you can run it locally using the following command:

```shell

$ python my_example.py

```

Alternatively, you can run the task locally with the `{{< key cli >}}` command line tool:

To run it locally, you can use the following `{{< key cli >}} run` command:

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} run my_example.py my_workflow --a 1 --b 2 --c 3 --m 4 --n 5

```

This has the advantage of allowing you to specify the input values as command line arguments.

For more details on running workflows and tasks, see **Development cycle**.

### Running a task or workflow remotely on the command line with `{{< key cli >}}`

To run a workflow remotely on your {{< key product_name >}} installation, use the following command (this assumes that you have your **Development cycle > Setting up a production project**):

```shell

$ {{< key cli >}} run --remote my_example.py my_workflow --a 1 --b 2 --c 3 --m 4 --n 5

```

### Running a task or workflow remotely in Python with `{{< key kit_remote >}}`

To run a workflow or task remotely in Python, use the method [`{{< key kit_remote >}}.execute`](). See [`{{< key kit_remote >}}`]() for more options and details.

## Subpages

- **Core concepts > Workflows**

- **Core concepts > Tasks**

- **Core concepts > Launch plans**

- **Core concepts > Actors**

- **Core concepts > Artifacts**

- **Core concepts > App Serving**

- **Core concepts > Caching**

- **Core concepts > Workspaces**

- **Core concepts > Named outputs**

- **Core concepts > ImageSpec**

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/workflows ===

# Workflows

So far in our discussion of workflows, we have focused on top-level workflows decorated with `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow`.

These are, in fact, more accurately termed **Core concepts > Workflows > Standard workflows** to differentiate them from the other types of workflows that exist in {{< key product_name >}}: **Core concepts > Workflows > Subworkflows and sub-launch plans**, **Core concepts > Workflows > Dynamic workflows**, and **Core concepts > Workflows > Imperative workflows**.

In this section, we will delve deeper into the fundamentals of all of these workflow types, including their syntax, structure, and behavior.

## Subpages

- **Core concepts > Workflows > Standard workflows**

- **Core concepts > Workflows > Subworkflows and sub-launch plans**

- **Core concepts > Workflows > Dynamic workflows**

- **Core concepts > Workflows > Imperative workflows**

- **Core concepts > Workflows > Launching workflows**

- **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflows**

- **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflow executions**

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/workflows/standard-workflows ===

# Standard workflows

A standard workflow is defined by a Python function decorated with the `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` decorator.

The function is written in a domain specific language (DSL), a subset of Python syntax that describes the directed acyclic graph (DAG) that is deployed and executed on {{< key product_name >}}.

The syntax of a standard workflow definition can only include the following:

* Calls to functions decorated with `@{{< key kit_as >}}.task` and assignment of variables to the returned values.

* Calls to other functions decorated with `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` and assignment of variables to the returned values (see **Core concepts > Workflows > Subworkflows and sub-launch plans**).

* Calls to **Core concepts > Launch plans** (see **Core concepts > Workflows > Subworkflows and sub-launch plans > When to use sub-launch plans**)

* Calls to functions decorated with `@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic` and assignment of variables to the returned values (see **Core concepts > Workflows > Dynamic workflows**).

* The special **Programming > Conditionals**.

* Statements using the **Programming > Chaining Entities**.

## Evaluation of a standard workflow

When a standard workflow is **Core concepts > Workflows > Standard workflows > run locally in a Python environment** it is executed as a normal Python function.

However, when it is registered to {{< key product_name >}}, the top level `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow`-decorated function is evaluated as follows:

* Inputs to the workflow are materialized as lazily-evaluated promises which are propagated to downstream tasks and subworkflows.

* All values returned by calls to functions decorated with `@{{< key kit_as >}}.task` or `@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic` are also materialized as lazily-evaluated promises.

The resulting structure is used to construct the Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) and deploy the required containers to the cluster.

The actual evaluation of these promises occurs when the tasks (or dynamic workflows) are executed in their respective containers.

## Conditional construct

Because standard workflows cannot directly include Python `if` statements, a special `conditional` construct is provided that allows you to define conditional logic in a workflow.

For details, see **Programming > Conditionals**.

## Chaining operator

When {{< key product_name >}} builds the DAG for a standard workflow, it uses the passing of values from one task to another to determine the dependency relationships between tasks.

There may be cases where you want to define a dependency between two tasks that is not based on the output of one task being passed as an input to another.

In that case, you can use the chaining operator `>>` to define the dependencies between tasks.

For details, see **Programming > Chaining Entities**.

## Workflow decorator parameters

The `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` decorator can take the following parameters:

* `failure_policy`: Use the options in **Flytekit SDK**.

* `on_failure`: Invoke this workflow or task on failure. The workflow specified must have the same parameter signature as the current workflow, with an additional parameter called `error`.

* `docs`: A description entity for the workflow.

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/workflows/subworkflows-and-sub-launch-plans ===

# Subworkflows and sub-launch plans

In {{< key product_name >}} it is possible to invoke one workflow from within another.

A parent workflow can invoke a child workflow in two ways: as a **subworkflow** or via a **Core concepts > Launch plans > Running launch plans > Sub-launch plans**.

In both cases the child workflow is defined and registered normally, exists in the system normally, and can be run independently.

But, if the child workflow is invoked from within the parent **by directly calling the child's function**, then it becomes a **subworkflow**.

The DAG of the subworkflow is embedded directly into the DAG of the parent and effectively become part of the parent workflow execution, sharing the same execution ID and execution context.

On the other hand, if the child workflow is invoked from within the parent **Core concepts > Launch plans**, this is called a **sub-launch plan**. It results in a new top-level workflow execution being invoked with its own execution ID and execution context.

It also appears as a separate top-level entity in the system.

The only difference is that it happens to have been kicked off from within another workflow instead of from the command line or the UI.

Here is an example:

```python

import {{< key kit_import >}}

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def sub_wf(a: int, b: int) -> int:

return t(a=a, b=b)

# Get the default launch plan of sub_wf, which we name sub_wf_lp

sub_wf_lp = {{< key kit_as >}}.LaunchPlan.get_or_create(sub_wf)

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def main_wf():

# Invoke sub_wf directly.

# An embedded subworkflow results.

sub_wf(a=3, b=4)

# Invoke sub_wf through its default launch plan, here called sub_wf_lp

# An independent subworkflow results.

sub_wf_lp(a=1, b=2)

```

## When to use subworkflows

Subworkflows allow you to manage parallelism between a workflow and its launched sub-flows, as they execute within the same context as the parent workflow.

Consequently, all nodes of a subworkflow adhere to the overall constraints imposed by the parent workflow.

Here's an example illustrating the calculation of slope, intercept and the corresponding y-value.

```python

import {{< key kit_import >}}

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def slope(x: list[int], y: list[int]) -> float:

sum_xy = sum([x[i] * y[i] for i in range(len(x))])

sum_x_squared = sum([x[i] ** 2 for i in range(len(x))])

n = len(x)

return (n * sum_xy - sum(x) * sum(y)) / (n * sum_x_squared - sum(x) ** 2)

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def intercept(x: list[int], y: list[int], slope: float) -> float:

mean_x = sum(x) / len(x)

mean_y = sum(y) / len(y)

intercept = mean_y - slope * mean_x

return intercept

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def slope_intercept_wf(x: list[int], y: list[int]) -> (float, float):

slope_value = slope(x=x, y=y)

intercept_value = intercept(x=x, y=y, slope=slope_value)

return (slope_value, intercept_value)

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def regression_line(val: int, slope_value: float, intercept_value: float) -> float:

return (slope_value * val) + intercept_value # y = mx + c

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def regression_line_wf(val: int = 5, x: list[int] = [-3, 0, 3], y: list[int] = [7, 4, -2]) -> float:

slope_value, intercept_value = slope_intercept_wf(x=x, y=y)

return regression_line(val=val, slope_value=slope_value, intercept_value=intercept_value)

```

The `slope_intercept_wf` computes the slope and intercept of the regression line.

Subsequently, the `regression_line_wf` triggers `slope_intercept_wf` and then computes the y-value.

It is possible to nest a workflow that contains a subworkflow within yet another workflow.

Workflows can be easily constructed from other workflows, even if they also function as standalone entities.

For example, each workflow in the example below has the capability to exist and run independently:

```python

import {{< key kit_import >}}

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def nested_regression_line_wf() -> float:

return regression_line_wf()

```

## When to use sub-launch plans

Sub-launch plans can be useful for implementing exceptionally large or complicated workflows that can’t be adequately implemented as **Core concepts > Workflows > Dynamic workflows** or **Core concepts > Workflows > Subworkflows and sub-launch plans > map tasks**.

Dynamic workflows and map tasks share the same context and single underlying Kubernetes resource definitions.

Sub-launch plan invoked workflows do not share the same context.

They are executed as separate top-level entities, allowing for better parallelism and scale.

Here is an example of invoking a workflow multiple times through its launch plan:

```python

import {{< key kit_import >}}

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def my_task(a: int, b: int, c: int) -> int:

return a + b + c

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def my_workflow(a: int, b: int, c: int) -> int:

return my_task(a=a, b=b, c=c)

my_workflow_lp = {{< key kit_as >}}.LaunchPlan.get_or_create(my_workflow)

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def wf() -> list[int]:

return [my_workflow_lp(a=i, b=i, c=i) for i in [1, 2, 3]]

```

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/workflows/dynamic-workflows ===

# Dynamic workflows

A workflow whose directed acyclic graph (DAG) is computed at run-time is a [`dynamic`]() workflow.

The tasks in a dynamic workflow are executed at runtime using dynamic inputs. A dynamic workflow shares similarities with the [`workflow`](), as it uses a Python-esque domain-specific language to declare dependencies between the tasks or define new workflows.

A key distinction lies in the dynamic workflow being assessed at runtime. This means that the inputs are initially materialized and forwarded to the dynamic workflow, resembling the behavior of a task. However, the return value from a dynamic workflow is a [`Promise`]() object, which can be materialized by the subsequent tasks.

Think of a dynamic workflow as a combination of a task and a workflow. It is used to dynamically decide the parameters of a workflow at runtime and is both compiled and executed at run-time.

Dynamic workflows become essential when you need to do the following:

- Handle conditional logic

- Modify the logic of the code at runtime

- Change or decide on feature extraction parameters on the fly

## Defining a dynamic workflow

You can define a dynamic workflow using the `@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic` decorator.

Within the `@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic` context, each invocation of a [`task`]() or a derivative of the [`Task`]() class leads to deferred evaluation using a Promise, rather than the immediate materialization of the actual value. While nesting other `@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic` and `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` constructs within this task is possible, direct interaction with the outputs of a task/workflow is limited, as they are lazily evaluated. If you need to interact with the outputs, we recommend separating the logic in a dynamic workflow and creating a new task to read and resolve the outputs.

The example below uses a dynamic workflow to count the common characters between any two strings.

We define a task that returns the index of a character, where A-Z/a-z is equivalent to 0-25:

```python

import {{< key kit_import >}}

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def return_index(character: str) -> int:

if character.islower():

return ord(character) - ord("a")

else:

return ord(character) - ord("A")

```

We also create a task that prepares a list of 26 characters by populating the frequency of each character:

```python

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def update_list(freq_list: list[int], list_index: int) -> list[int]:

freq_list[list_index] += 1

return freq_list

```

We define a task to calculate the number of common characters between the two strings:

```python

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def derive_count(freq1: list[int], freq2: list[int]) -> int:

count = 0

for i in range(26):

count += min(freq1[i], freq2[i])

return count

```

We define a dynamic workflow to accomplish the following:

1. Initialize an empty 26-character list to be passed to the `update_list` task.

2. Iterate through each character of the first string (`s1`) and populate the frequency list.

3. Iterate through each character of the second string (`s2`) and populate the frequency list.

4. Determine the number of common characters by comparing the two frequency lists.

The looping process depends on the number of characters in both strings, which is unknown until runtime:

```python

@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic

def count_characters(s1: str, s2: str) -> int:

# s1 and s2 should be accessible

# Initialize empty lists with 26 slots each, corresponding to every alphabet (lower and upper case)

freq1 = [0] * 26

freq2 = [0] * 26

# Loop through characters in s1

for i in range(len(s1)):

# Calculate the index for the current character in the alphabet

index = return_index(character=s1[i])

# Update the frequency list for s1

freq1 = update_list(freq_list=freq1, list_index=index)

# index and freq1 are not accessible as they are promises

# looping through the string s2

for i in range(len(s2)):

# Calculate the index for the current character in the alphabet

index = return_index(character=s2[i])

# Update the frequency list for s2

freq2 = update_list(freq_list=freq2, list_index=index)

# index and freq2 are not accessible as they are promises

# Count the common characters between s1 and s2

return derive_count(freq1=freq1, freq2=freq2)

```

A dynamic workflow is modeled as a task in the {{< key product_name >}} backend, but the body of the function is executed to produce a workflow at runtime. In both dynamic and static workflows, the output of tasks are Promise objects.

{{< key product_name >}} executes the dynamic workflow within its container, resulting in a compiled DAG, which is then accessible in the UI. It uses the information acquired during the dynamic task's execution to schedule and execute each task within the dynamic workflow. Visualization of the dynamic workflow's graph in the UI is only available after it has completed its execution.

When a dynamic workflow is executed, it generates the entire workflow structure as its output, termed the *futures file*.

This name reflects the fact that the workflow has yet to be executed, so all subsequent outputs are considered futures.

> [!NOTE]

> Local execution works when a `@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic` decorator is used because {{< key kit_name >}} treats it as a task that runs with native Python inputs.

Finally, we define a standard workflow that triggers the dynamic workflow:

```python

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def start_wf(s1: str, s2: str) -> int:

return count_characters(s1=s1, s2=s2)

```

You can run the workflow locally as follows:

```python

if __name__ == "__main__":

print(start_wf(s1="Pear", s2="Earth"))

```

## Advantages of dynamic workflows

### Flexibility

Dynamic workflows streamline the process of building pipelines, offering the flexibility to design workflows

according to the unique requirements of your project. This level of adaptability is not achievable with static workflows.

### Lower pressure on `etcd`

The workflow Custom Resource Definition (CRD) and the states associated with static workflows are stored in `etcd`,

the Kubernetes database. This database maintains {{< key product_name >}} workflow CRDs as key-value pairs, tracking the status of each node's execution.

However, `etcd` has a hard limit on data size, encompassing the workflow and node status sizes, so it is important to ensure that static workflows don't excessively consume memory.

In contrast, dynamic workflows offload the workflow specification (including node/task definitions and connections) to the object store. Still, the statuses of nodes are stored in the workflow CRD within `etcd`.

Dynamic workflows help alleviate some pressure on `etcd` storage space, providing a solution to mitigate storage constraints.

## Dynamic workflows vs. map tasks

Dynamic tasks come with overhead for large fan-out tasks as they store metadata for the entire workflow.

In contrast, **Core concepts > Workflows > Dynamic workflows > map tasks** prove efficient for such extensive fan-out scenarios since they refrain from storing metadata, resulting in less noticeable overhead.

## Using dynamic workflows to achieve recursion

Merge sort is a perfect example to showcase how to seamlessly achieve recursion using dynamic workflows.

{{< key product_name >}} imposes limitations on the depth of recursion to prevent misuse and potential impacts on the overall stability of the system.

```python

from typing import Tuple

import {{< key kit_import >}}

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def split(numbers: list[int]) -> tuple[list[int], list[int]]:

length = len(numbers)

return (

numbers[0 : int(length / 2)],

numbers[int(length / 2) :]

)

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def merge(sorted_list1: list[int], sorted_list2: list[int]) -> list[int]:

result = []

while len(sorted_list1) > 0 and len(sorted_list2) > 0:

# Compare the current element of the first array with the current element of the second array.

# If the element in the first array is smaller, append it to the result and increment the first array index.

# Otherwise, do the same with the second array.

if sorted_list1[0] < sorted_list2[0]:

result.append(sorted_list1.pop(0))

else:

result.append(sorted_list2.pop(0))

# Extend the result with the remaining elements from both arrays

result.extend(sorted_list1)

result.extend(sorted_list2)

return result

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def sort_locally(numbers: list[int]) -> list[int]:

return sorted(numbers)

@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic

def merge_sort_remotely(numbers: list[int], threshold: int) -> list[int]:

split1, split2 = split(numbers=numbers)

sorted1 = merge_sort(numbers=split1, threshold=threshold)

sorted2 = merge_sort(numbers=split2, threshold=threshold)

return merge(sorted_list1=sorted1, sorted_list2=sorted2)

@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic

def merge_sort(numbers: list[int], threshold: int=5) -> list[int]:

if len(numbers) <= threshold:

return sort_locally(numbers=numbers)

else:

return merge_sort_remotely(numbers=numbers, threshold=threshold)

```

By simply adding the `@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic` annotation, the `merge_sort_remotely` function transforms into a plan of execution,

generating a workflow with four distinct nodes. These nodes run remotely on potentially different hosts,

with {{< key product_name >}} ensuring proper data reference passing and maintaining execution order with maximum possible parallelism.

`@{{< key kit_as >}}.dynamic` is essential in this context because the number of times `merge_sort` needs to be triggered is unknown at compile time. The dynamic workflow calls a static workflow, which subsequently calls the dynamic workflow again,

creating a recursive and flexible execution structure.

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/workflows/imperative-workflows ===

# Imperative workflows

Workflows are commonly created by applying the `@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow` decorator to Python functions.

During compilation, this involves processing the function's body and utilizing subsequent calls to

underlying tasks to establish and record the workflow structure. This is the *declarative* approach

and is suitable when manually drafting the workflow.

However, in cases where workflows are constructed programmatically, an imperative style is more appropriate.

For instance, if tasks have been defined already, their sequence and dependencies might have been specified in textual form (perhaps during a transition from a legacy system).

In such scenarios, you want to orchestrate these tasks.

This is where {{< key product_name >}}'s imperative workflows come into play, allowing you to programmatically construct workflows.

## Example

To begin, we define the `slope` and `intercept` tasks:

```python

import {{< key kit_import >}}

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def slope(x: list[int], y: list[int]) -> float:

sum_xy = sum([x[i] * y[i] for i in range(len(x))])

sum_x_squared = sum([x[i] ** 2 for i in range(len(x))])

n = len(x)

return (n * sum_xy - sum(x) * sum(y)) / (n * sum_x_squared - sum(x) ** 2)

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def intercept(x: list[int], y: list[int], slope: float) -> float:

mean_x = sum(x) / len(x)

mean_y = sum(y) / len(y)

intercept = mean_y - slope * mean_x

return intercept

```

Create an imperative workflow:

```python

imperative_wf = Workflow(name="imperative_workflow")

```

Add the workflow inputs to the imperative workflow:

```python

imperative_wf.add_workflow_input("x", list[int])

imperative_wf.add_workflow_input("y", list[int])

```

> If you want to assign default values to the workflow inputs, you can create a **Core concepts > Launch plans**.

Add the tasks that need to be triggered from within the workflow:

```python

node_t1 = imperative_wf.add_entity(slope, x=imperative_wf.inputs["x"], y=imperative_wf.inputs["y"])

node_t2 = imperative_wf.add_entity(

intercept, x=imperative_wf.inputs["x"], y=imperative_wf.inputs["y"], slope=node_t1.outputs["o0"]

)

```

Lastly, add the workflow output:

```python

imperative_wf.add_workflow_output("wf_output", node_t2.outputs["o0"])

```

You can execute the workflow locally as follows:

```python

if __name__ == "__main__":

print(f"Running imperative_wf() {imperative_wf(x=[-3, 0, 3], y=[7, 4, -2])}")

```

You also have the option to provide a list of inputs and

retrieve a list of outputs from the workflow:

```python

wf_input_y = imperative_wf.add_workflow_input("y", list[str])

node_t3 = wf.add_entity(some_task, a=[wf.inputs["x"], wf_input_y])

wf.add_workflow_output(

"list_of_outputs",

[node_t1.outputs["o0"], node_t2.outputs["o0"]],

python_type=list[str],

)

```

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/workflows/launching-workflows ===

# Launching workflows

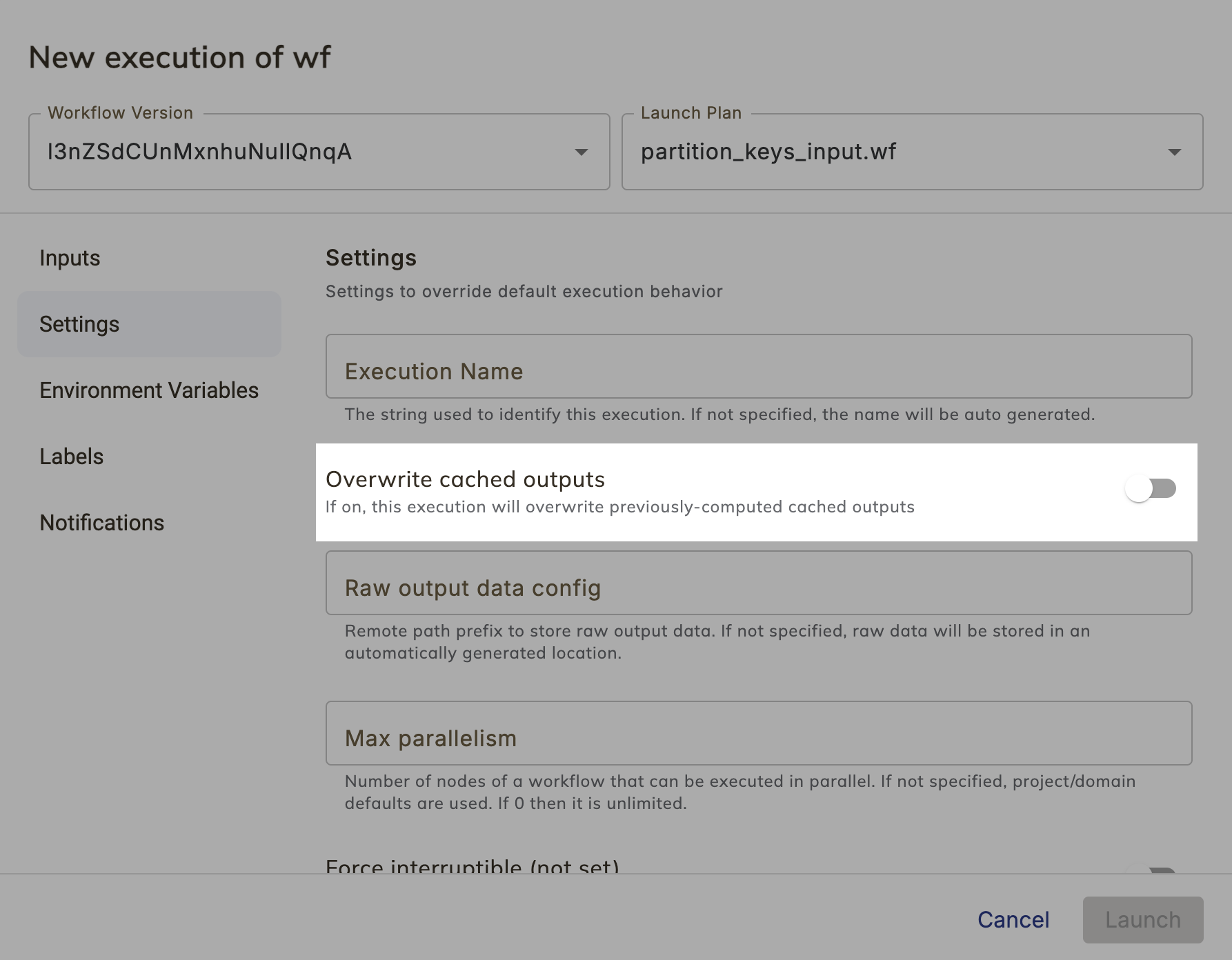

From the **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflows > Workflow view** (accessed, for example, by selecting a workflow in the **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflows > Workflows list**) you can select **Launch Workflow** in the top right. This opens the **New Execution** dialog for workflows:

At the top you can select:

* The specific version of this workflow that you want to launch.

* The launch plan to be used to launch this workflow (by default it is set to the **Core concepts > Launch plans > Default launch plan**).

Along the left side the following sections are available:

* **Inputs**: The input parameters of the workflow function appear here as fields to be filled in.

* **Settings**:

* **Execution name**: A custom name for this execution. If not specified, a name will be generated.

* **Overwrite cached outputs**: A boolean. If set to `True`, this execution will overwrite any previously-computed cached outputs.

* **Raw output data config**: Remote path prefix to store raw output data.

By default, workflow output will be written to the built-in metadata storage.

Alternatively, you can specify a custom location for output at the organization, project-domain, or individual execution levels.

This field is for specifying this setting at the workflow execution level.

If this field is filled in it overrides any settings at higher levels.

The parameter is expected to be a URL to a writable resource (for example, `http://s3.amazonaws.com/my-bucket/`).

See **Data input/output > Task input and output > Raw data store**.

* **Max parallelism**: Number of workflow nodes that can be executed in parallel. If not specified, project/domain defaults are used. If 0 then no limit is applied.

* **Force interruptible**: A three valued setting for overriding the interruptible setting of the workflow for this particular execution.

If not set, the workflow's interruptible setting is used.

If set and **enabled** then `interruptible=True` is used for this execution.

If set and **disabled** then `interruptible=False` is used for this execution.

See **Core concepts > Tasks > Task hardware environment > Interruptible instances**

* **Environment variables**: Environment variables that will be available to tasks in this workflow execution.

* **Labels**: Labels to apply to the execution resource.

* **Notifications**: **Core concepts > Launch plans > Notifications** configured for this workflow execution.

Select **Launch** to launch the workflow execution. This will take you to the **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflow executions**.

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/workflows/viewing-workflows ===

# Viewing workflows

## Workflows list

The workflows list shows all workflows in the current project and domain:

You can search the list by name and filter for only those that are archived.

To archive a workflow, select the archive icon .

Each entry in the list provides some basic information about the workflow:

* **Last execution time**:

The time of the most recent execution of this workflow.

* **Last 10 executions**:

The status of the last 10 executions of this workflow.

* **Inputs**:

The input type for the workflow.

* **Outputs**:

The output type for the workflow.

* **Description**:

The description of the workflow.

Select an entry on the list to go to that **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflows > Workflow view**.

## Workflow view

The workflow view provides details about a specific workflow.

This view provides:

* A list of recent workflow versions:

Selecting a version will take you to the **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflows > Workflow view > Workflow versions list**.

* A list of recent executions:

Selecting an execution will take you to the **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflow executions**.

### Workflow versions list

The workflow versions list shows the a list of all versions of this workflow along with a graph view of the workflow structure:

### Workflow and task descriptions

{{< key product_name >}} enables the use of docstrings to document your code. Docstrings are stored in the control plane and displayed on the UI for each workflow or task.

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/workflows/viewing-workflow-executions ===

# Viewing workflow executions

The **Executions list** shows all executions in a project and domain combination.

An execution represents a single run of all or part of a workflow (including subworkflows and individual tasks).

You can access it from the **Executions** link in the left navigation.

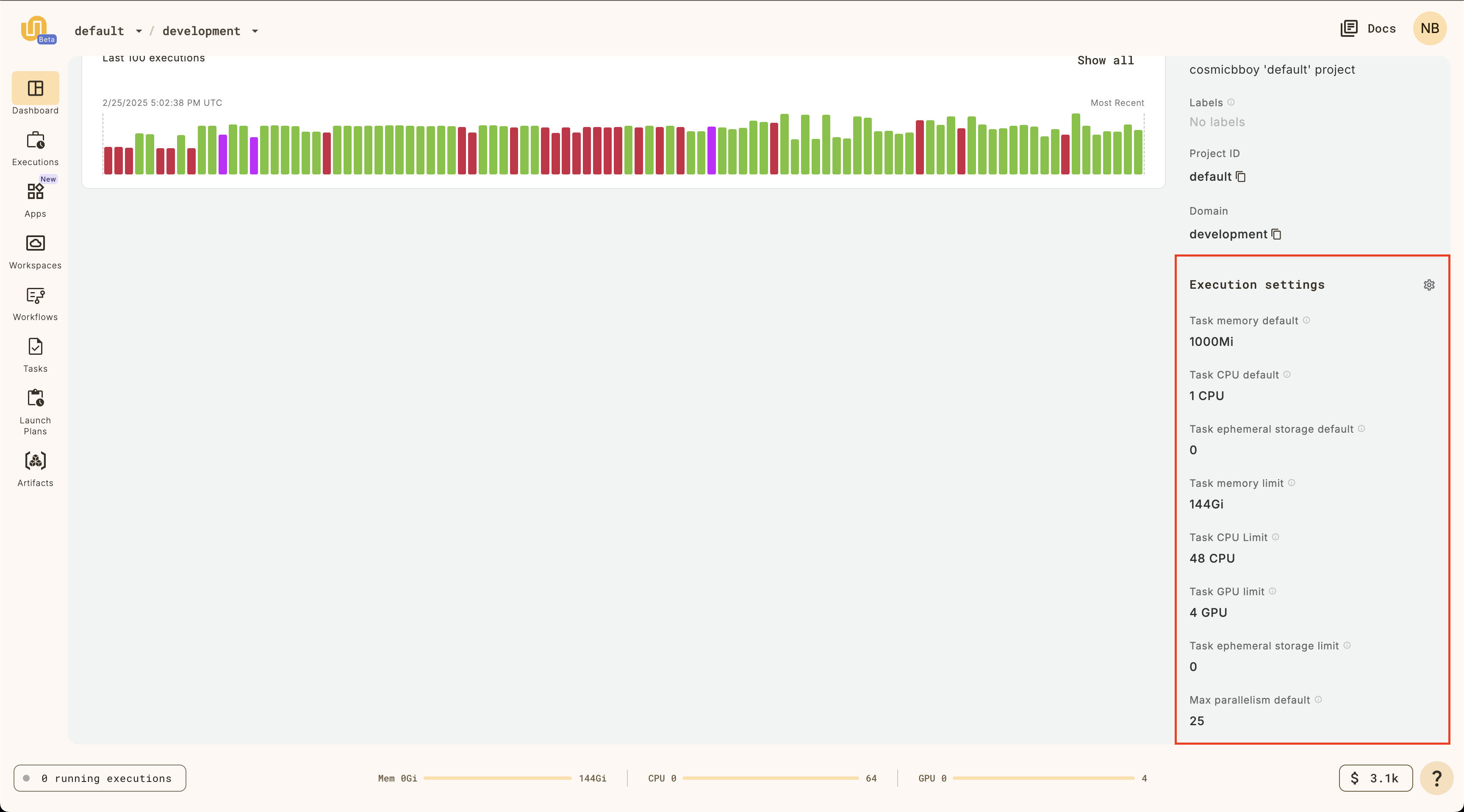

## Domain Settings

This section displays any domain-level settings that have been configured for this project-domain combination. They are:

* Security Context

* Labels

* Annotations

* Raw output data config

* Max parallelism

## All Executions in the Project

For each execution in this project and domain you can see the following:

* A graph of the **last 100 executions in the project**.

* **Start time**: Select to view the **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflow executions > Execution view**.

* **Workflow/Task**: The **Core concepts > Workflows > Viewing workflows** or **Core concepts > Tasks > Viewing tasks** that ran in this execution.

* **Version**: The version of the workflow or task that ran in this execution.

* **Launch Plan**: The **Core concepts > Launch plans > Viewing launch plans** that was used to launch this execution.

* **Schedule**: The schedule that was used to launch this execution (if any).

* **Execution ID**: The ID of the execution.

* **Status**: The status of the execution. One of **QUEUED**, **RUNNING**, **SUCCEEDED**, **FAILED** or **UNKNOWN**.

* **Duration**: The duration of the execution.

## Execution view

The execution view appears when you launch a workflow or task or select an already completed execution.

An execution represents a single run of all or part of a workflow (including subworkflows and individual tasks).

> [!NOTE]

> An execution usually represents the run of an entire workflow.

> But, because workflows are composed of tasks (and sometimes subworkflows) and {{< key product_name >}} caches the outputs of those independently of the workflows in which they participate, it sometimes makes sense to execute a task or subworkflow independently.

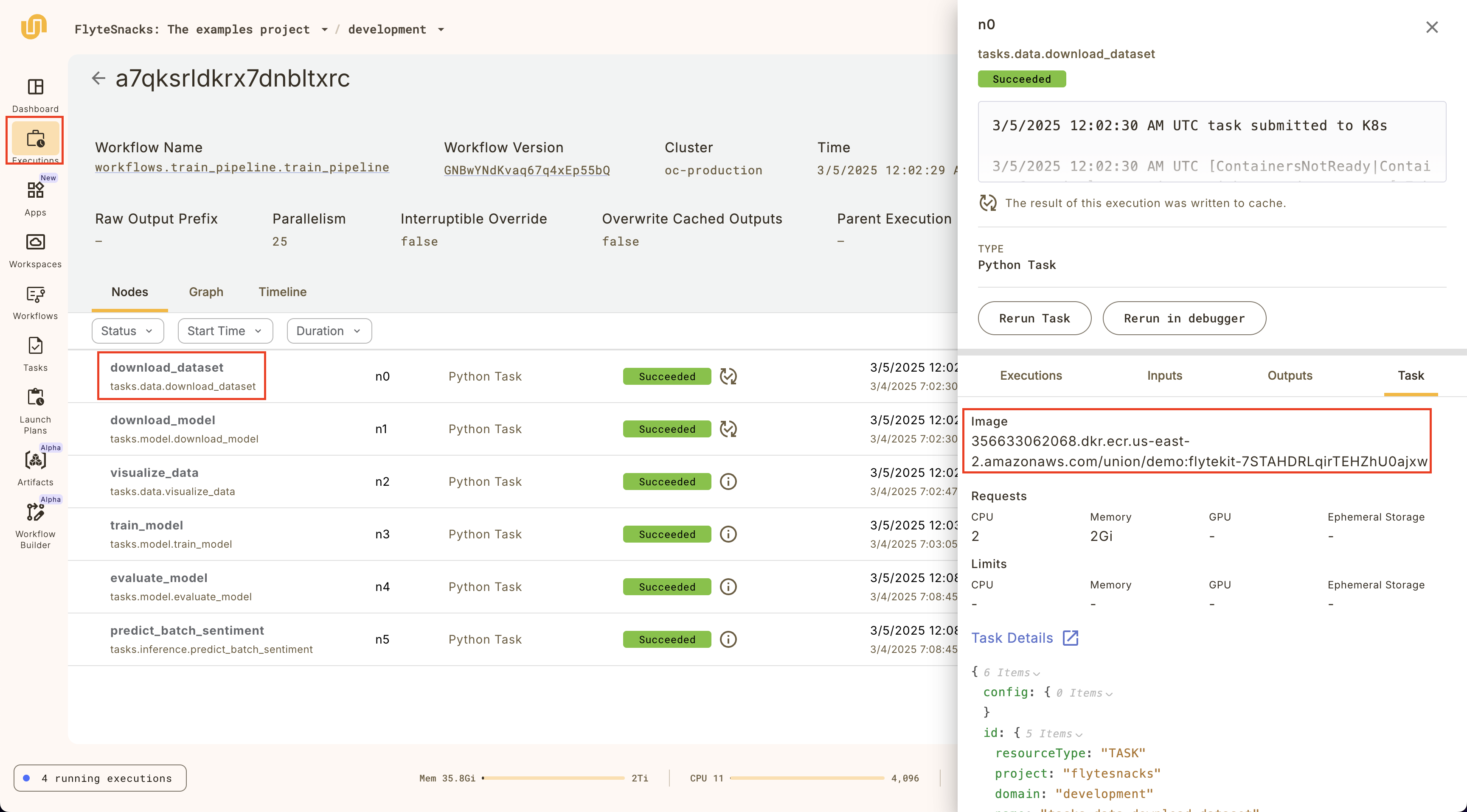

The top part of execution view provides detailed general information about the execution.

The bottom part provides three tabs displaying different aspects of the execution: **Nodes**, **Graph**, and **Timeline**.

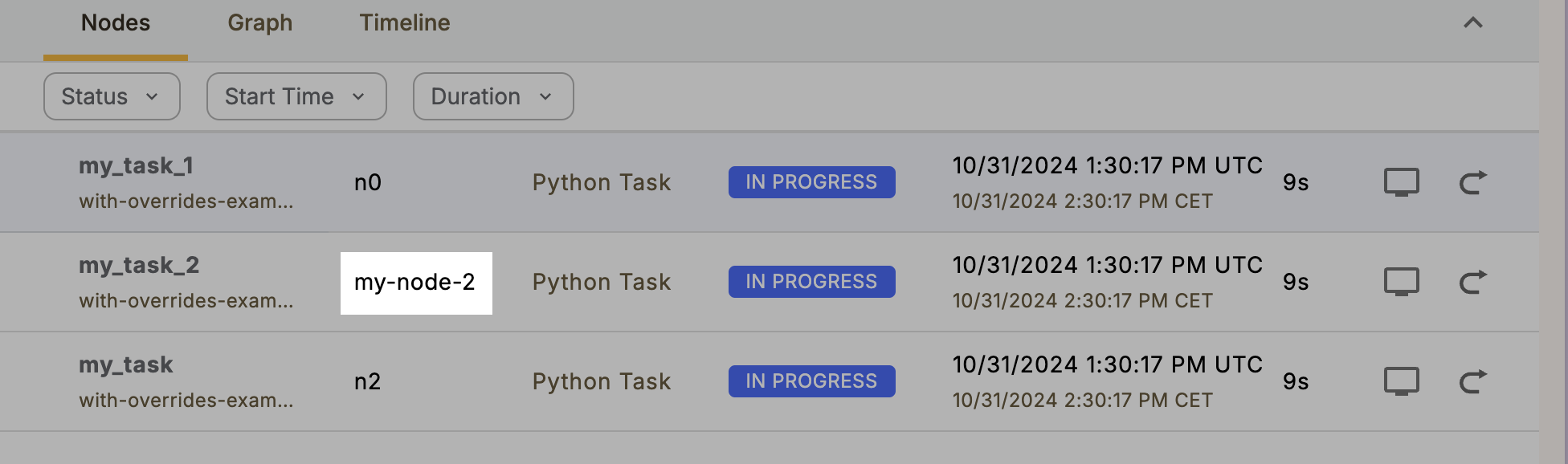

### Nodes

The default tab within the execution view is the **Nodes** tab.

It shows a list of the {{< key product_name >}} nodes that make up this execution (A node in {{< key product_name >}} is either a task or a (sub-)workflow).

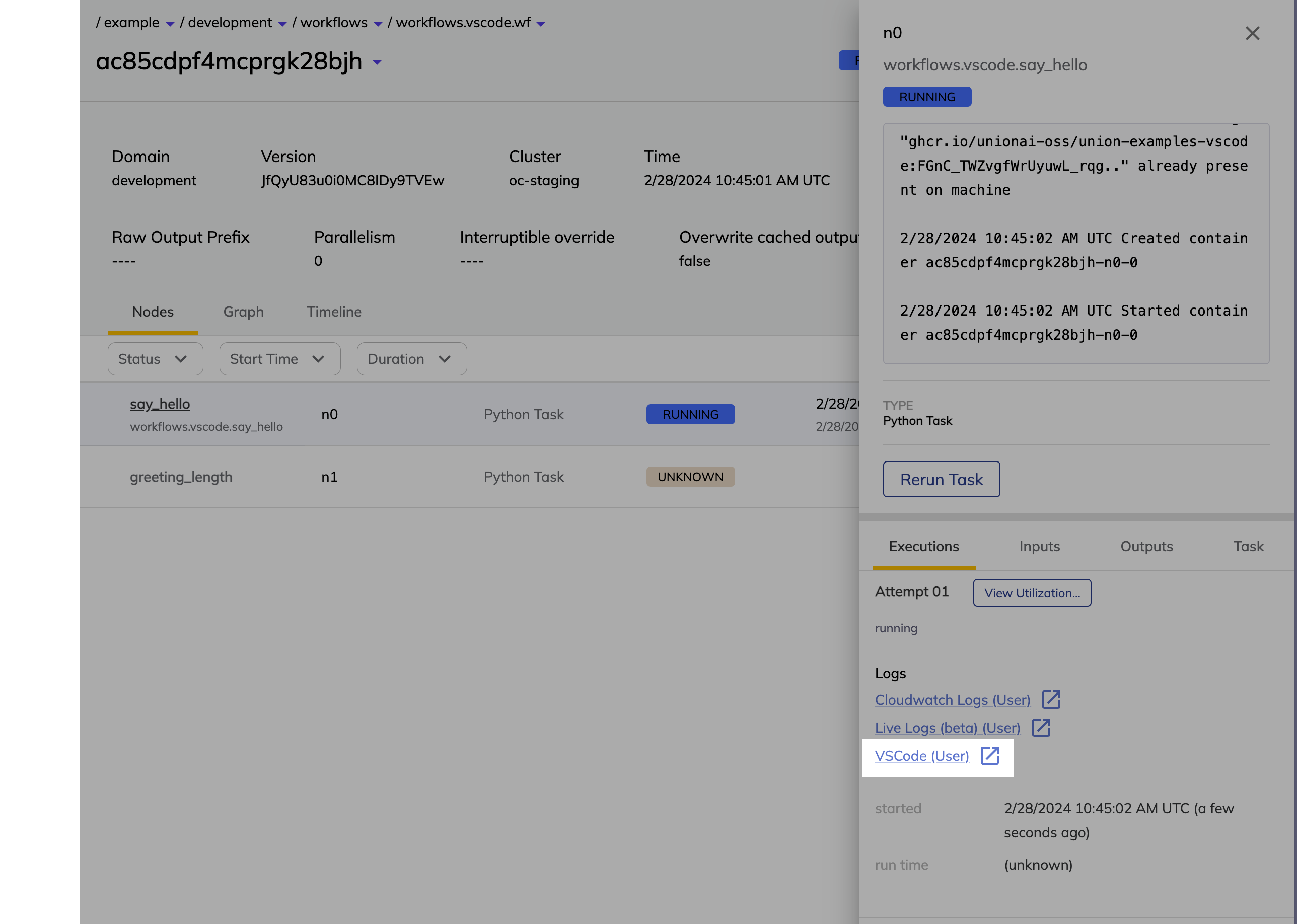

Selecting an item in the list opens the right panel showing more details of that specific node:

The top part of the side panel provides detailed information about the node as well as the **Rerun task** button.

Below that, you have the following tabs: **Executions**, **Inputs**, **Outputs**, and **Task**.

The **Executions** tab gives you details on the execution of this particular node as well as access to:

* **Task level monitoring**: You can access the **Core concepts > Tasks > Task hardware environment > Task-level monitoring** information by selecting **View Utilization**.

* **Logs**: You can access logs by clicking the text under **Logs**. See **Core concepts > Tasks > Viewing logs**.

The **Inputs**, **Outputs** tabs display the data that was passed into and out of the node, respectively.

If this node is a task (as opposed to a subworkflow) then the **Task** tab displays the Task definition structure.

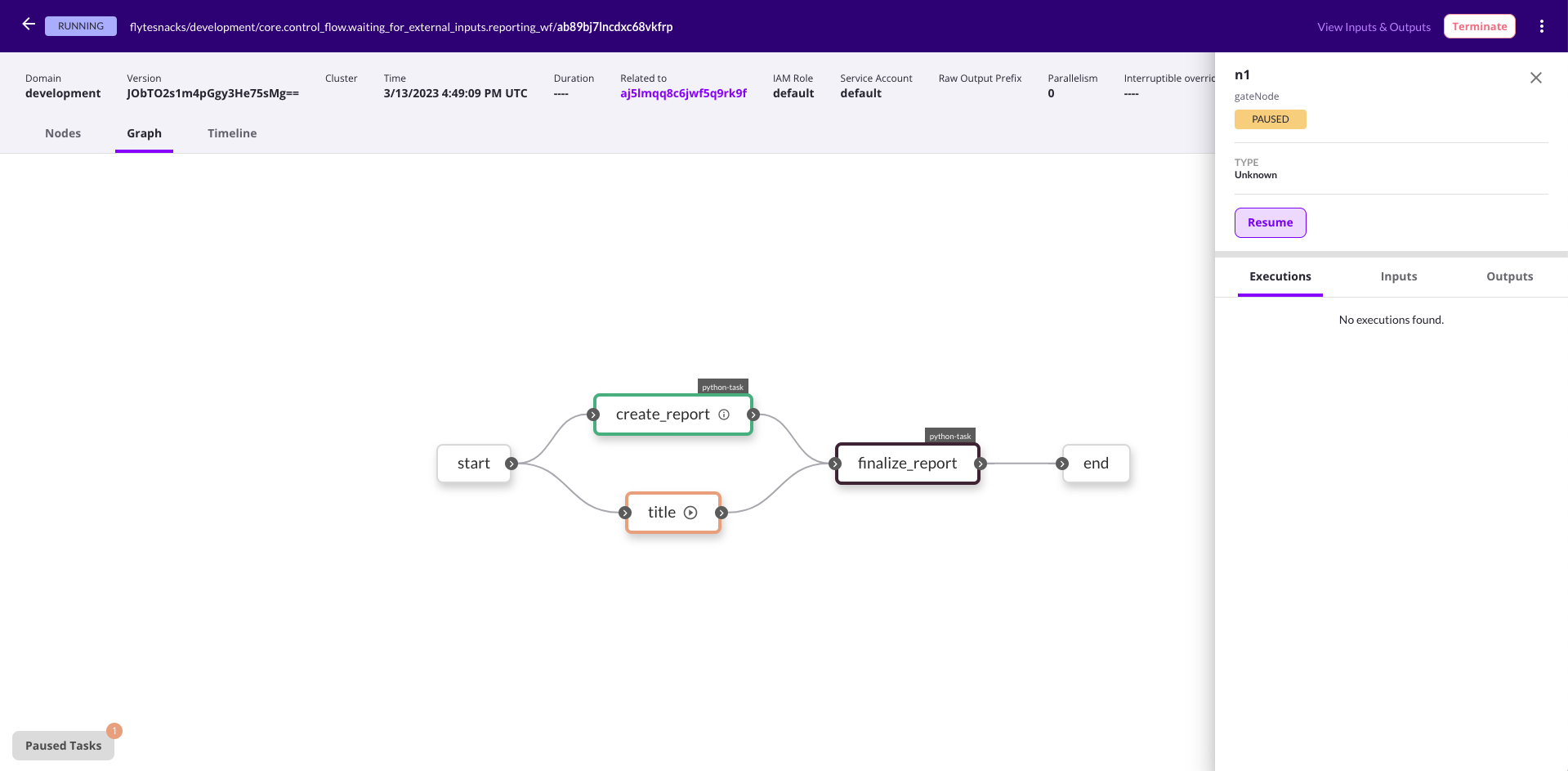

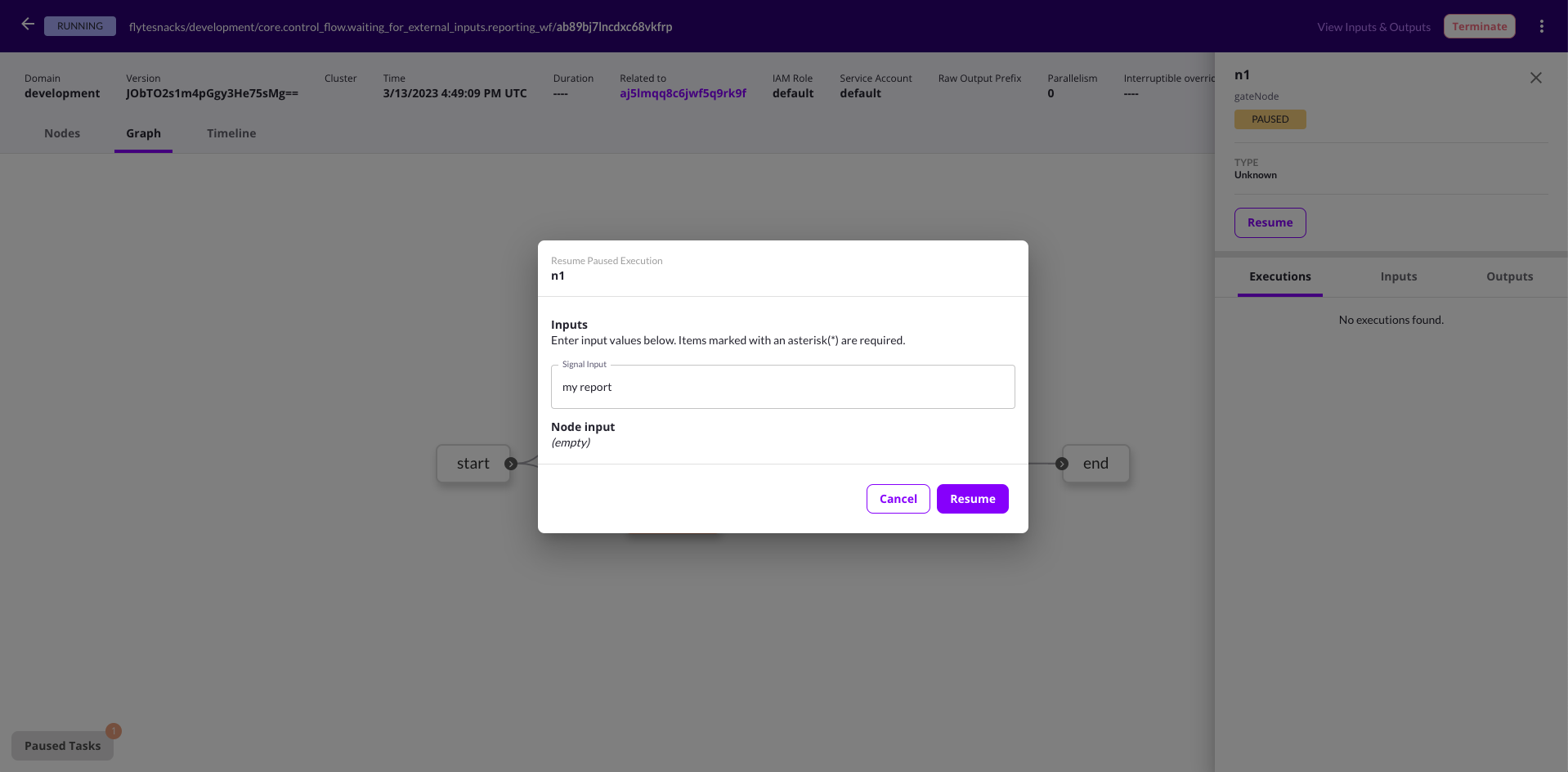

### Graph

The Graph tab displays a visual representation of the execution as a directed acyclic graph:

### Timeline

The Timeline tab displays a visualization showing the timing of each task in the execution:

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/tasks ===

# Tasks

Tasks are the fundamental units of compute in {{< key product_name >}}.

They are independently executable, strongly typed, and containerized building blocks that make up workflows.

Workflows are constructed by chaining together tasks, with the output of one task feeding into the input of the next to form a directed acyclic graph.

## Tasks are independently executable

Tasks are designed to be independently executable, meaning that they can be run in isolation from other tasks.

And since most tasks are just Python functions, they can be executed on your local machine, making it easy to unit test and debug tasks locally before deploying them to {{< key product_name >}}.

Because they are independently executable, tasks can also be shared and reused across multiple workflows and, as long as their logic is deterministic, their input and outputs can be **Core concepts > Caching** to save compute resources and execution time.

## Tasks are strongly typed

Tasks have strongly typed inputs and outputs, which are validated at deployment time.

This helps catch bugs early and ensures that the data passing through tasks and workflows is compatible with the explicitly stated types.

Under the hood, {{< key product_name >}} uses the [Flyte type system]() and translates between the Flyte types and the Python types.

Python type annotations make sure that the data passing through tasks and workflows is compatible with the explicitly stated types defined through a function signature.

The {{< key product_name >}} type system is also used for caching, data lineage tracking, and automatic serialization and deserialization of data as it’s passed from one task to another.

## Tasks are containerized

While (most) tasks are locally executable, when a task is deployed to {{< key product_name >}} as part of the registration process it is containerized and run in its own independent Kubernetes pod.

This allows tasks to have their own independent set of **Core concepts > ImageSpec** and [hardware requirements](./task-hardware-environment/_index).

For example, a task that requires a GPU can be deployed to {{< key product_name >}} with a GPU-enabled container image, while a task that requires a specific version of a software library can be deployed with that version of the library installed.

## Tasks are named, versioned, and immutable

The fully qualified name of a task is a combination of its project, domain, and name. To update a task, you change it and re-register it under the same fully qualified name. This creates a new version of the task while the old version remains available. At the version level task are, therefore, immutable. This immutability is important for ensuring that workflows are reproducible and that the data lineage is accurate.

## Tasks are (usually) deterministic and cacheable

When deciding if a unit of execution is suitable to be encapsulated as a task, consider the following questions:

* Is there a well-defined graceful/successful exit criteria for the task?

* A task is expected to exit after completion of input processing.

* Is it deterministic and repeatable?

* Under certain circumstances, a task might be cached or rerun with the same inputs.

It is expected to produce the same output every time.

You should, for example, avoid using random number generators with the current clock as seed.

* Is it a pure function? That is, does it have side effects that are unknown to the system?

* It is recommended to avoid side effects in tasks.

* When side effects are unavoidable, ensure that the operations are idempotent.

For details on task caching, see **Core concepts > Caching**.

## Subpages

- **Core concepts > Tasks > Map Tasks**

- **Core concepts > Tasks > Other task types**

- **Core concepts > Tasks > Task parameters**

- **Core concepts > Tasks > Launching tasks**

- **Core concepts > Tasks > Viewing tasks**

- **Core concepts > Tasks > Viewing logs**

- **Core concepts > Tasks > Reference tasks**

- **Core concepts > Tasks > Task hardware environment**

=== PAGE: https://www.union.ai/docs/v1/serverless/user-guide/core-concepts/tasks/map-tasks ===

## Map tasks

A map task allows you to execute many instances of a task within a single workflow node.

This enables you to execute a task across a set of inputs without having to create a node for each input, resulting in significant performance improvements.

Map tasks find application in various scenarios, including:

* When multiple inputs require running through the same code logic.

* Processing multiple data batches concurrently.

Just like normal tasks, map tasks are automatically parallelized to the extent possible given resources available in the cluster.

```python

THRESHOLD = 11

@{{< key kit_as >}}.task

def detect_anomalies(data_point: int) -> bool:

return data_point > THRESHOLD

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def map_workflow(data: list[int] = [10, 12, 11, 10, 13, 12, 100, 11, 12, 10]) -> list[bool]:

# Use the map task to apply the anomaly detection function to each data point

return {{< key kit_as >}}.{{< key map_func >}}(detect_anomalies)(data_point=data)

```

> [!NOTE]

> Map tasks can also map over launch plans. For more information and example code, see **Core concepts > Launch plans > Mapping over launch plans**.

To customize resource allocations, such as memory usage for individual map tasks, you can leverage `with_overrides`. Here’s an example using the `detect_anomalies` map task within a workflow:

```python

import union

@{{< key kit_as >}}.workflow

def map_workflow_with_resource_overrides(

data: list[int] = [10, 12, 11, 10, 13, 12, 100, 11, 12, 10]

) -> list[bool]:

return (

{{< key kit_as >}}.{{< key map_func >}}(detect_anomalies)(data_point=data)

.with_overrides(requests={{< key kit_as >}}.Resources(mem="2Gi"))

)

```